Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, breaking news, sweepstakes, and more!

How NYC Man’s 1990 Murder Became State’s First Anti-Gay Hate Crime Conviction

Three youths with "bad intentions" brutally murdered Julio Rivera in a case that forever changed how the N.Y.P.D. tackled crimes against the LGBTQ+ community.

It was the height of the A.I.D.S. pandemic in New York City, when fear and misunderstanding turned into hate, especially against members of the LGBTQ+ community. When violence hit the culturally diverse neighborhood of Jackson Heights, Queens, the N.Y.P.D. had to adjust their accustomed methods of investigation to find who brutally murdered a gay man one Fourth of July weekend.

It was around 3:00 a.m. on July 2, 1990, when 29-year-old Julio Rivera left his life partner, Alan Sack, with a mutual friend and headed down a Queens street. Moments later, a panicked man approached Sack and the friend, screaming someone was being murdered just down the road.

“Never in my wildest dreams did I think that it was Julio,” Sack said in a video obtained by New York Homicide, airing Saturdays at 9/8c on Oxygen.

Sack and his friend ran to Rivera, who was “about to pass out” and “covered in blood,” according to Sack. One or more people had attacked Rivera in the schoolyard of P.S. 69 on 37th Avenue; however, Rivera could not identify his attacker(s) before succumbing to his injuries at a local hospital.

RELATED: Detectives Search for Fake Doctor Suspected of Killing Missing Manhattan Banker

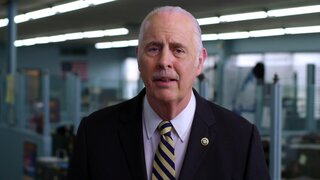

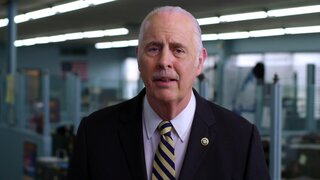

N.Y.P.D. officers from the 115th Precinct were well-familiar with P.S. 69, then a hot spot for crimes like drug dealing and prostitution, according to Deputy Inspector Mark Magrone of the Hate Crimes Task Force.

“The dark schoolyard, it’s sort of the perfect place for a crime,” Magrone told New York Homicide.

Detectives at the crime scene, including Detective Jacob Habib, noted a broken bottle on the street. Beyond that, police had little physical evidence to go on and no apparent witnesses to the crime.

A postmortem examination later revealed Rivera was beaten in the face and head with at least one blunt object, though the fatal injury was a knife wound through the back that caused a punctured lung. Toxicology reports also showed the presence of cocaine in Rivera’s system, which led N.Y.P.D. officers to the premature theory that Rivera’s murder was drug-related.

Rivera’s lover and relatives did not buy into police’s theory.

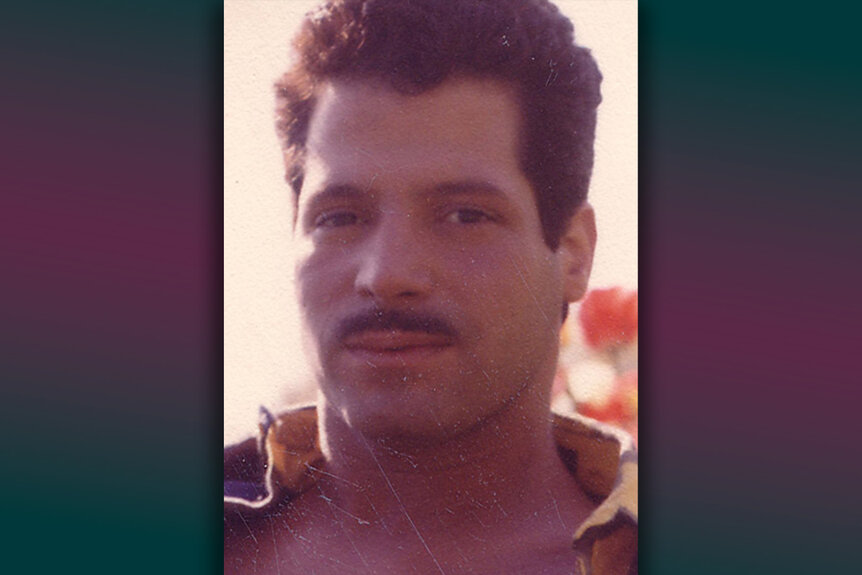

Who was Julio Rivera?

Rivera was a Puerto Rican man from the Bronx, described by his sister-in-law, Peggy Fiori, as “a lot of fun.”

“He was so extraordinarily handsome,” Fiori told New York Homicide. “He always was true to himself.”

Julio grew up in “the projects,” according to Fiori, and struggled with homophobic bullying while at school, resulting in his abandoning his education. Soon, however, he found a community with other LGBTQ+ people in Queens, where he worked as a bartender.

“Julio was happy to find life in Jackson Heights,” continued Fiori. “And be loved by anyone who had time to spend with him.”

The LGBTQ+ Community Pushes for Answers

Those who knew Rivera best didn’t subscribe to the theory that he died in a drug-related attack. Members of the LGBTQ+ community mostly believed Rivera’s homicide was part of ongoing anti-gay violence, according to Richard Shpuntoff, Director at Julio of Jackson Heights.

“They were like, ‘No, no, we know what the story is, we know this is an area of illicit activity, we’re following what makes the most sense to us,’” Shpuntoff told New York Homicide.

Alan Sack also didn’t believe his partner died because of drugs, saying Rivera was “slaughtered” for being gay. He reached out to the area’s Anti-Violence Project, hoping workers – such as former executive director Matt Foreman — could help persuade the N.Y.P.D. to adjust their lines of inquiry on the basis that Rivera’s murder was a hate crime.

Foreman said that, back in 1990, many endorsed anti-gay violence because of the “demonization” of people living with A.I.D.S. Politicians and church protesters, especially, viewed gay people as “disease spreaders.”

“The block or two around P.S. 69 was a gay cruising area,” Foreman told New York Homicide. “So, it was a place where if you wanted to beat up a gay person, that’s where you’d go. Everyone knew that.”

Together, Sack and Foreman petitioned the police. When their pleas were met with no response, the men rallied other LGBTQ+ members and advocates and took their campaign to the streets, creating Jackson Heights’ first LGBTQ+ march. Hundreds came, and the push for justice soon landed at the literal doorstep of then-Mayor David Dinkins.

“An attack against one of us is an attack against all of us,” said Sack.

Thanks to public pressure, the Queens District Attorney’s Office assigned N.Y.P.D. Lieutenant George Byrd to the case.

A New Witness and an Undercover Cop

Five months after Rivera’s vicious murder, Lt. Byrd “went after this case with relentless pursuit,” according to Sack.

“When I got involved in this particular case, I reached out to the gay community and also the area in which this crime took place,” Byrd told New York Homicide. “I was able to talk to them in such a way that they were comfortable enough and that they would trust me to do the right thing.”

Byrd’s approach worked, and soon, a witness named Tony came forward with information. Tony, a gay sex worker, said he saw a long-haired male approach Julio. Around that time, Tony left to work, but when he returned a short time later, he saw three men — the long-haired man and two skinheads — running away from the crime scene.

RELATED: Maitre D's Slaying on New York City’s “Restaurant Row” Helps Solve Cold Case Murder

Tony gave a good description of the men, including one of the suspects’ double-headed eagle tattoo and two of them in Doc Martens boots. One man had a hammer, and another had a wrench, weapons that perfectly matched Rivera’s wounds.

“There was word in the street that there was a group of skinheads who were trying to establish a form of control in Jackson Heights,” Byrd said. “And they were known as D.M.S.”

D.M.S. — which stood for Doc Martens Skinheads — was a small and unorganized criminal outfit with a penchant for graffitiing buildings. They were not known to the N.Y.P.D.’s gang unit.

According to Byrd, D.M.S. was less of a white supremacist group and more of an anti-gay outfit.

Byrd went undercover, bringing his personal Harley Davidson motorcycle and a jean jacket to the Kennedy Bar, where D.M.S. associates were rumored to hang out. After a few drinks with an informant named “Army Dan,” Byrd learned the suspects were Daniel Doyle, 20, Esat Bici, 18, and Erik Brown, 21.

Police Learn New Info About the Suspects

Brown — the one cops believed was the long-haired man — had cut his hair before being brought in for questioning. Bici, a high school honors student of Albanian descent, had let his hair grow out, as did Doyle, the son of a former N.Y.P.D. Detective.

Bici also had a double-headed eagle tattoo, matching the symbol of the Albanian flag.

The three young men denied having any role or knowledge of Julio Rivera’s murder and were subsequently released. But the police persisted.

Tony, Lt. Byrd’s eyewitness, picked all three suspects from a photo lineup. Since Bici and Brown retained legal representation, investigators hoped to reach Doyle by appealing to his law enforcement father.

“I laid the cards on the table,” said Byrd. “I said to him, ‘Look, either Danny Doyle was gonna take the fall for this by himself, or he was going to work out some type of cooperation agreement with the D.A.’s Office.’”

On November 13, 1990, police interrogated Doyle, as seen in a video published by New York Homicide. Per a deal with Queens prosecutors, Doyle confessed to the events surrounding Julio Rivera’s murder.

Doyle said he had an “informal gathering” at his home, with him, Bici, and Brown being the last-remaining guests of the evening. He said he grabbed a claw hammer, pipe wrench, and thin-bladed knife from his father’s toolbox, divvying the tools-turned-weapons.

“They had bad intentions when they left the house,” said Lt. Byrd. “So, basically, it was a hunting party.”

RELATED: Two Young Women with Big City Dreams Found Dead in Upper West Side Double Murder

The group saw Rivera by P.S. 69 when Doyle told Brown to go to Rivera and ask for sex in exchange for drugs. Bici first hit Rivera in the head with a beer bottle before drawing the hammer, though Doyle issued the fatal wound by using the knife to stab him once in the back. Brown beat Rivera with the plumber’s wrench “as hard and fast as he could,” Doyle told detectives.

“[Doyle] told me there was hatred for the gay community,” Byrd told New York Homicide. “They didn’t want to see this in their community, so what do you do? Let’s exterminate them; let’s get them outta here.”

Doyle agreed to testify against the other two suspects in exchange for pleading guilty to manslaughter.

It would be the first time anyone was tried and convicted for an anti-gay hate crime in the state of New York.

The Convictions and Aftermath

“It was so horrific to hear Danny Doyle describe the details of the murder,” said Rivera’s sister-in-law, Peggy Fiori. “It’s beyond our comprehension to do that to a human being.”

In 1991, after three days of jury deliberations, Bici and Brown were convicted of second-degree murder and sentenced to life in prison. Doyle, who’d pleaded guilty to lesser charges, was sentenced to a maximum of 25 years.

Matt Foreman, of the Anti-Violence Project, called the convictions a “monumental relief,” and loved ones and advocates from around the world gathered that night in Jackson Heights to commemorate the milestone.

“Julio’s murder brought to the forefront the violence against homosexuals in our community and in our nation,” Fiori told New York Homicide. “It was astounding, and it brought more stories to the surface. It allowed the police to take it more seriously. There was a tremendous impact.”

Rivera’s murder became why the N.Y.P.D. opened a unit specifically dealing with crimes against the LGBTQ+ community.

Watch all-new New York Homicide Saturdays at 9/8c on Oxygen.