Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, breaking news, sweepstakes, and more!

How An Author's Murder Was Connected To One Of America's Richest And Well-Known Killers

In "Blood & Money," LAPD investigators recall the Christmastime 2000 murder of Susan Berman and the cases ties to the 20-year-old disappearance of the wife of Robert Durst.

It seemed money would be no issue when one of America’s most well-known convicted killers hired the best defense team money could buy.

On Christmas Eve, Dec. 24, 2000, Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) officers were dispatched to a Benedict Canyon home in Los Angeles. Neighbors grew concerned when they found a dog belonging to Susan Berman, 55, wandering the road, soon finding Berman’s back door open and delivered packages never collected.

Inside the home, former LAPD patrol officer Rashad Sharif found Berman dead on the floor, having sustained a single gunshot wound to the back of the head, a murder that appeared to be a mob-style hit. Experts concluded she’d been dead for 24 to 36 hours, giving her killer a head start.

RELATED: How Susan Berman And Robert Durst Were Connected

“We later found out [Berman] was a daughter of a guy that used to own a hotel in Vegas back in the 40s or 50s,” Sharif told "Blood & Money," airing Saturdays at 9/8c on Oxygen. “Was she killed because she was connected to Vegas?”

According to retired LAPD Detective Supervisor Paul Coulter, Berman’s father was the Chief Financial Officer for the Jewish mafia in Las Vegas. Berman’s mother was a showgirl, and upon her parents’ passing — when Berman was still a young child — she inherited a sizable sum that “should have taken her through her whole life,” said Berman’s cousin, Deni Marcus.

“Her trust fund, at the time of her mother’s death, was somewhere between four and five million, but Susie had a character flaw: she was loyal, and she loved her friends,” said Marcus. “She was an orphan, and she’d do anything to create her own family of friends, and people took advantage of it. That money became a trap.”

Berman, a writer, burned through her inheritance by the time she began renting a home in Benedict Canyon, moving to the City of Angels in hopes of finding commercial success as an author, but to no avail.

“At that point, everything was gone,” said Marcus. “She was sleeping on a mattress on the floor, so she was living very, very minimally.”

At the onset of the investigation, investigators looked into three possible theories, the first revolving around witness statements that Berman was cooking up a big mob-related story for a book she planned to write. The second possible suspect was Berman’s landlady due to Berman being months behind with her rent.

A third possible suspect was Berman’s manager, whom detectives believed hung around waiting for Berman to catch a big writing break that would never come.

But there was a twist in the investigation when police in Beverly Hills received an anonymous letter with the word “cadaver” written inside, along with Berman’s address. The letter was postmarked Christmas Day, one day after Susan was found dead.

The word “Beverly” on the envelope’s address was misspelled as “Beverley.”

Returning to the crime scene soon after the new year, LAPD investigators encountered law enforcement officials from New York state.

“We learned Susan Berman was a person they wanted to interview,” Det. Coulter told "Blood & Money."

Retired New York State Investigator Joseph Becerra explained they wanted to talk to Berman about her long-time friend, Robert “Bob” Durst, who was suspected of killing his wife, Kathleen Durst, nearly 20 years earlier. In January 2001, they arrived in Benedict Canyon, hoping to conduct a surprise visit, only then learning of Berman’s murder.

Kathleen Durst disappeared on Feb. 1, 1982, from her South Salem, New York home, which she shared with Robert, who came from a billion-dollar real estate family based in New York City. At the time, Robert told police he dropped Kathleen off at the Katonah train station because she wanted to head to the city, where she attended medical school.

The next day, a woman purporting to be Kathleen reportedly called the school, claiming she was too sick to attend class.

After reopening the case in 2000, New York State investigators believed Robert could be behind Kathleen’s disappearance, allegedly motivated by the pair’s impending divorce and Robert resisting the idea of a payout.

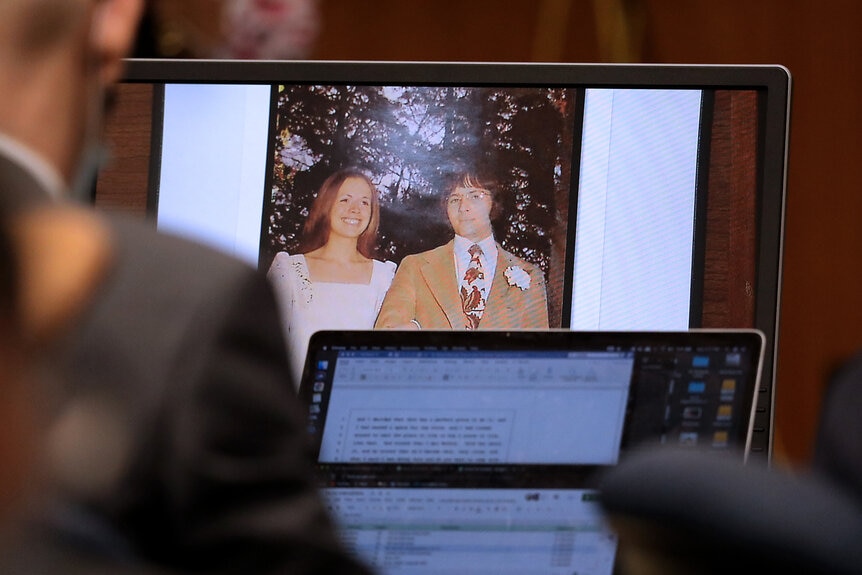

Berman, who met Robert Durst while attending UCLA in the late 1960s, was close with the Dursts, and even stayed in the spare bedroom of one of their New York City penthouses in the 1970s.

Investigators hoped Robert confided in Berman about Kathleen’s disappearance.

“The fact that shortly before we’re going to interview her, she’s found dead in her home, I could not help but think it was him,” Becerra stated.

Berman’s friends spoke highly of Robert Durst, and soon, investigators found he’d given Berman tens of thousands of dollars to help her keep her head above water while living in Los Angeles. By all accounts, Durst was a good friend, prompting detectives to shift their focus back to mobsters, the landlady, and Berman’s so-called manager.

But the mobsters Berman alluded to in her 1981 memoir “Easy Street” were well-gone or elderly. The landlady was also elderly and could not be connected to the murder, while the manager cooperated with officials.

Unlike Robert Durst, who was reportedly in San Francisco — a six-hour drive north of Los Angeles — when Berman died. Investigators from California and New York soon grew frustrated when nothing conclusively tied Durst to either his wife’s disappearance or Berman’s murder.

“And then Galveston happened,” Det. Coulter told "Blood & Money."

In October 2001, Westchester County officials in New York caught wind that Durst was arrested in Galveston, Texas. There, Durst disguised himself as a mute woman who rented a $400-a-month room in the same residence as Morris Black, whose dismembered body was found in Galveston Bay.

Investigators theorized that Durst revealed his true identity to Black, prompting him to later kill him and dispose of his body.

The case went to trial in 2003, and though forensic evidence pointing toward Durst killing and dismembering Black was overwhelming, Durst’s top-dollar defense team (for which he paid nearly $2 million) argued self-defense, claiming an armed Black approached Durst and that the pair wrestled for a gun that accidentally went off.

But because Black’s head was never found, the angle of the bullet couldn’t be proven, and ultimately, Durst was found not guilty of Black’s homicide.

“My jaw dropped,” said Becerra. “I just… I couldn’t believe it.”

Durst’s story was fictionalized in the 2010 Andrew Jarecki film “All Good Things,” starring Ryan Gosling and Kirsten Dunst. In response to the film, Durst reached out to Jarecki, who chronicled Durst’s story in the hit HBO 2015 documentary “The Jinx: The Lives and Deaths of Robert Durst.”

As part of the series production, Susan Berman’s stepson gave filmmakers a March 3, 1999, letter from Durst to Berman. The envelope’s address was misspelled to read “Beverley” Hills, as was the case in the Christmas Day 2000 letter meant to alert police that there was a “cadaver” at Berman’s residence. Both also had “identical” handwriting, according to Los Angeles County Deputy District Attorney John Lewin.

“I ended up being made aware of the [March 1999] note by Andrew [Jarecki] and Marc [Smerling],” said Lewin. “I had the cadaver note, and I also saw the footage where Durst was confronted. And it was extremely compelling.”

It was enough for Los Angeles County prosecutors to file murder charges against Durst for Susan Berman’s death, and he was arrested in New Orleans in March 2015. This time, Durst reportedly paid between $10 million and $12 million for his defense.

During pretrial, prosecutors brought in witnesses from New York who knew Berman and the Dursts. One claimed Berman approached her around the time of Kathleen Durst’s 1982 disappearance and said, “I did something today, and I did it for Bobby.”

Berman also allegedly said, “If anything ever happened to me, Bobby did it.”

Another witness claimed Berman admitted to calling the medical school where Kathleen attended and pretended to be Kathleen calling in sick.

“Susan ends up helping Bob, and she now has Bob under her control,” according to Dep. District Attorney Lewin.

Investigators believe Durst murdered Berman so that she couldn’t talk to detectives who’d reopened the case of Kathleen’s 1982 disappearance.

In March 2020, at the start of the trial, prosecutors had an uphill battle before them when up against Durst’s well-paid defense. Then, proceedings were delayed 14 months due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

In August 2021, a frail Durst — then confined to a wheelchair and wearing a neck brace — took the stand in his defense in an alleged attempt to garner the jury’s sympathy. In his testimony, Durst detailed his mother’s fatal fall from the roof of their Scarsdale, New York home when Durst was just 7 years old.

“I did not kill Susan Berman,” Durst said at trial. “But if I had, I would lie about it.”

Ultimately, in September 2021, the jury found Durst guilty of Susan Berman’s murder, and he was sentenced to life without the possibility of parole.

“This man robbed me and so many people of the most magnanimous human being,” said Berman’s cousin, Deni Marcus. “One of the most incredible characters that ever walked the earth.”

Robert Durst died of natural causes in January 2022 while in custody before he could face prosecution in New York for the 1982 death of Kathleen Durst. He was 78 years old.

Kathleen Durst’s body has never been found.

To learn more about the case, tune in to "Blood & Money" Saturdays at 9/8c on Oxygen. You can stream episodes here.