Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, breaking news, sweepstakes, and more!

Nearly 40 Years Ago, The Brutal And Fatal Beating Of An Asian American Man Fueled A Movement

The enduring legacy of Vincent Chin: His death changed the criminal justice system and ignited a civil rights movement for Asian Americans.

In conjunction with AAPI Heritage Month, Oxygen.com is highlighting the treatment of Asian Americans in the criminal justice system.

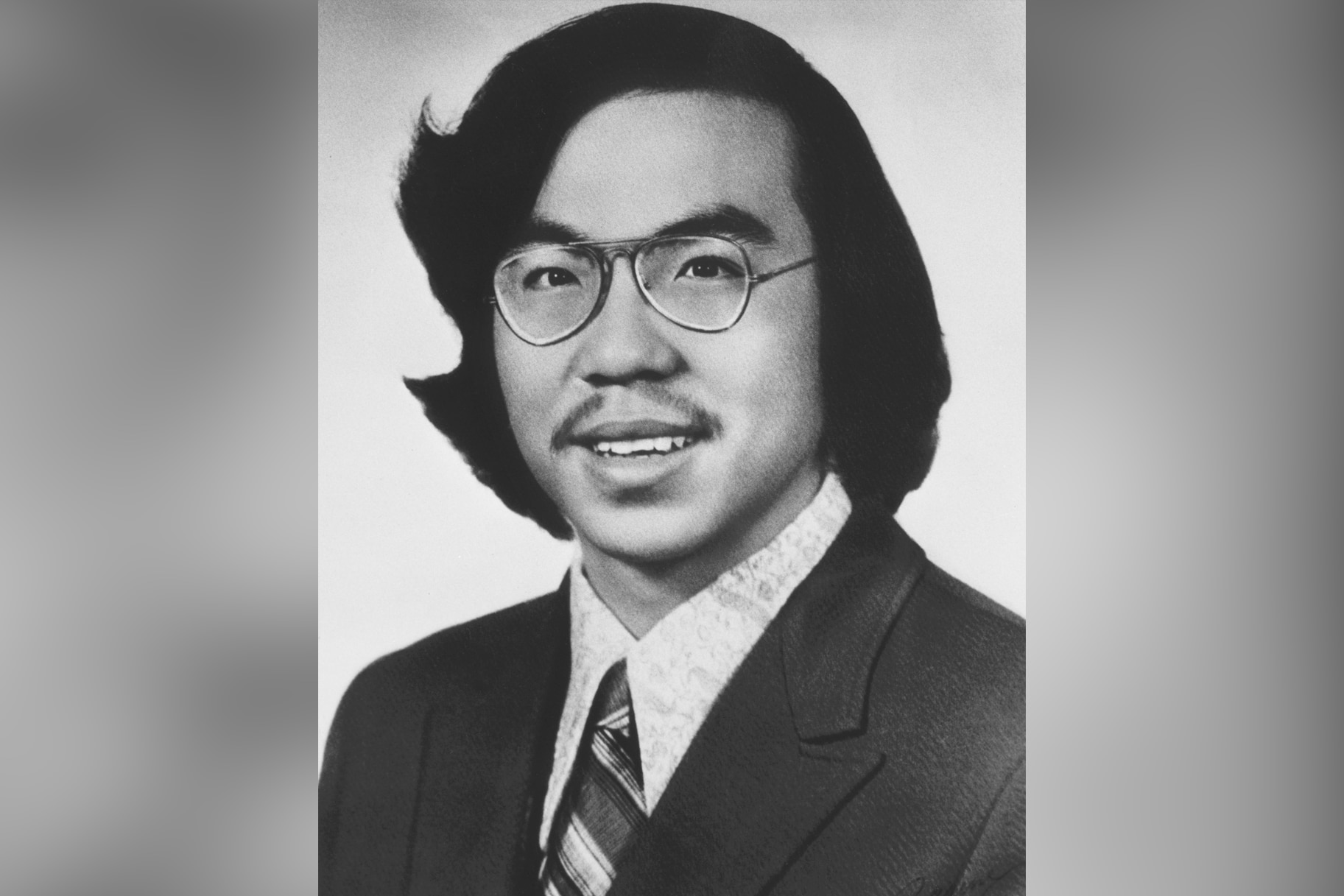

Nearly 40 years ago, on a warm night in June of 1982, Vincent Chin headed out for an impromptu bachelor party at a Detroit strip club, nine days before his wedding, but it ended in tragedy. Chin, an Asian American, was attacked by two white men and severely beaten with a baseball bat. He died four days later.

The last words Chin said on the night he was beaten before lapsing into a coma was “it’s not fair,” according to multiple media reports.

Family and friends gathered for his funeral on June 29, one day after he was supposed to wed the love of his life, Vikki Wong.

Chin, 27, was handsome, outgoing, and hardworking. He worked two jobs, as a draftsman at an engineering firm and a waiter at a Chinese restaurant to save money for his wedding.

He told his mother Lily Chin that this was to be “one last night out with the guys,” writes Paula Yoo, author of From A Whisper To A Rallying Cry: The Killing of Vincent Chin and the trial that Galvanized The Asian American Movement. The author reviewed thousands of pages of court documents and other materials.

Lily Chin was displeased with her son’s choice of words: “Don’t say ‘last time.’ It’s bad luck,” Yoo writes. Eight months earlier Lily had lost her husband, Bing Hong Chin, to kidney disease. The couple adopted Vincent from China at the age of 6, according to Yoo.

Chin and his best friends, Jimmy Choi, Gary Koivu and Bob Siroskey were at the Fancy Pants strip club when they encountered Ronald Ebens and his stepson, Michael Nitz. While urban legend depicts the men as unemployed auto workers, Ebens was a plant supervisor for Chrysler. Nitz had been laid off from his job at an auto factory, but was employed at a furniture store, according to the Vincent Chin 40th Rededication and Remembrance.

Yoo writes that a dancer moved away from Vincent and to Ebens’ table. He joked about feeling rejected and Ebens told him: “Boy, you don’t know a good thing when you see one.”

Vincent solemnly replied: “I am not a boy.”

A fight erupted and Vincent’s friends testified that racial slurs were hurled at them, but didn’t know who said them.

One of the dancers would later testify that Ebens shouted: “It’s because of you little (expletive) that we’re out of work.”

Ebens has vehemently denied using any racial slurs, calling the night a drunken brawl that got out of hand. Each group blamed the other for starting the fight. Nitz was bleeding profusely from a deep gash in his head after being hit with a chair. They were kicked out of the club.

“I was hoping once the fight broke up in the bar, that was it, that we’d both go our separate ways and go home,” Koivu told Yoo. “It didn’t turn out that way.”

They exchanged more words outside the club. Nitz grabbed a baseball bat out of his car. Ebens took the bat away from him and went after Vincen, who fled. Ebens chased him on foot, but eventually got in his car, searching for Vincent. He spotted him at a McDonald’s parking lot. He grabbed the bat, hitting Vincent repeatedly. By the time the ambulance arrived, parts of his brain were scattered across the street.

As doctors fought to save Vincent’s life, Ebens and Nitz were taken into custody. One day later, Ebens was charged with second-degree murder and released from jail without bond because he had no criminal record. Several days later, both Ebens and Nitz were charged with second-degree murder.

This unfolded as Detroit’s economy collapsed because the big three auto makers – Ford, Chrysler, and General Motors – were overtaken by Japanese car makers. Plants closed, people were laid off and bitter, fueling anti-Asian sentiment across the country, but especially in Detroit.

During a caucus meeting in March of 1982, the late Michigan congressman John Dingell described Japanese car companies as “the little yellow people,” according to the New York Times. He later apologized for the comment.

“It felt dangerous to have an Asian face,” journalist, activist and executor of Chin’s estate Helen Zia, writes in her memoir Asian American Dreams:The Emergence of An American People. “Asian American employees of auto companies were warned not to go onto the factory floor because angry workers might hurt them if they were thought to be Japanese.”

Ebens and Nitz pleaded guilty to manslaughter as part of a plea deal. Nine months after Vincent’s death, on March 16, 1983, they were sentenced to three years probation and ordered to pay nearly $4,000 in fines and court costs.

“They always admitted they did it. So, there’s no question that they killed someone brutally and never went to prison,” Frank Wu, the president of Queens College, City University of New York told Oxygen.com. “This is mistaken identity twice over. The killers were mad about Japan and Japanese cars…But Chin was Chinese, not Japaense. … He’s an American just like them. He’s working class, salt of the earth … His life is like his killers', except for the color of the skin, the texture of his hair, the shape of his eyes. He hangs out at the same places. He feels the same pinch of economic anxiety.”

Ebens and Nitz have always denied that the fight was racially motivated.

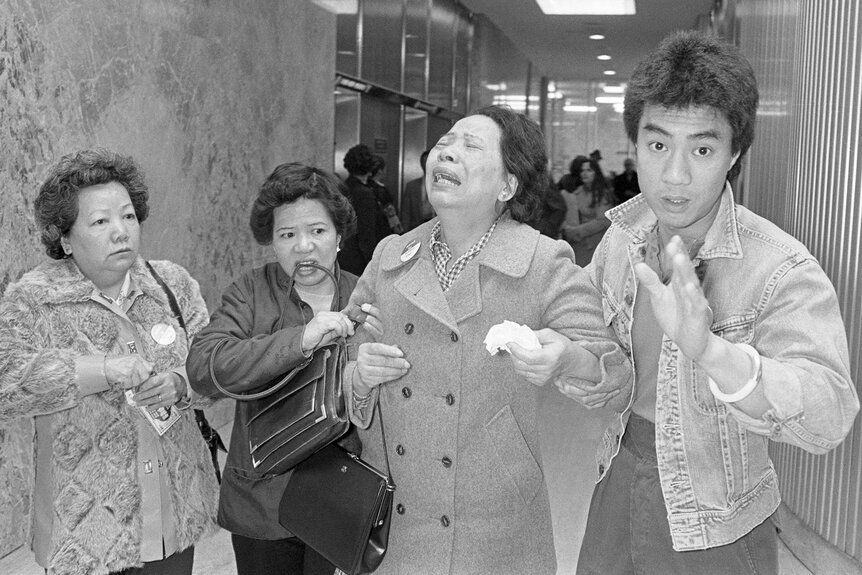

Vincent’s mother was not in the courtroom during the sentencing; even the prosecutors weren’t present. The judge only heard from the attorneys representing Ebens and Nitz and their side of the story. The case would eventually lead to widespread use of victim impact statements and stronger hate crime laws.

Explaining his reasoning for the sentence, Judge Charles Kaufman said: “We’re talking about a man who’s held down a responsible job with the same company for 17 or 18 years and his son who is employed and is a part-time student. These men are not going to go out and harm somebody else. I just didn’t think putting them in prison would do any good for them or for society. You don’t make the punishment fit the crime; you make the punishment fit the criminal.”

Chin’s death and the lenient sentencing shocked and galvanized the Asian American community fed up with tolerating decades of racism and xenophobia. They were joined by others black, white, and brown, in protests around the nation demanding justice for Vincent Chin.

"The (criminal justice) system didn't care," Detroit Mayor Mike Duggan told the Detroit News earlier this month. "It was a deep lesson, something we're learning to this day, that the system acts differently depending on the color of your skin."

“That was the springboard for the modern Asian American civil rights movement," Zia told the Detroit News. "Detroit was its epicenter."

“Until the Vincent Chin case, there was never a quote unquote national network or movement among Asian groups. What this case did in large part was get people from very diverse backgrounds to unite behind a cause,” Jim Shimoura, an attorney, told Oxygen.com. “If you notice, anytime people talk about any use of violence (against Asian Americans) they site this incident because it was the first to get national exposure.”

In March of 1983, Shimoura, Zia and Roland Hwang were among a core group of individuals who founded American Citizens for Justice in response to the case.

“People of all different Asian backgrounds realized that it really didn’t matter to people whether they were Chinese or Japanese or Korean or Vietnamese, that because they looked a certain way, they could be targeted for violence. And so, it was kind of a wakeup call to a lot of folks within the Asian-American community that they needed to band together,” Ian Shin, assistant professor of history of at the University of Michigan, told Oxygen.com.

The American Citizens for Justice and others were able to convince Kaufman to hold a hearing to reconsider the sentencing. He upheld it. Kaufman had a reputation as a liberal justice, but some in the Asian American community suspected he was biased because he was a prisoner of war in Japan during World War II, Yoo writes. Kaufman disputed the claim.

Lily Chin demanded justice for her son, giving interviews and traveling across the country, even appearing on the Phil Donahue Show.

“She is primarily a non-English speaker from a very modest background and all of a sudden she is thrust onto the national stage,” Shimoura said. “Imagine having to tell the story of how your son was beaten to death with a baseball bat over and over again like that, but she was determined to seek justice for her son.”

“The other thing about this case that is so important is … these guys weren’t KKK members. They weren’t skinheads. They didn’t go out that night thinking and saying, ‘Hey, let’s catch an Asian dude and kill him,” said Wu, then a teenager in the Detroit area. ”That makes it worse. If they were skinheads, you could avoid them. You could see them coming. It’s scarier if you go to a bar … and it’s a normal guy who just snaps.”

The Department of Justice intervened, with the FBI launching an investigation in April 1983. A federal grand jury indicted Ebens and Nitz for interfering with Vincent’s right to be in a place of public accommodation and with conspiracy, according to court documents reviewed by CNN. The case was groundbreaking. It was the first time the DOJ prosecuted a case using civil rights laws for the murder of an Asian American.

Defense attorneys for both men stressed that manslaughter was not equivalent to racism.

“There’s nothing in Ebens' background, nothing that his friends ever told us or even the FBI, that he even has any animosity toward Asian Americans,” Frank Eaman, one of the attorneys representing Ebens told Yoo in From A Whisper To A Rallying Cry. Yet he stands as the symbol or the scapegoat for Asian American violence. No one ever stopped to considered who Ron Ebens was.”

But prosecutors were adamant that the murder was racially motivated.

“This was more than some barroom brawl gone out of control,” Theodore Merritt said during his closing arguments, according to Yoo. “This was violent hatred turned loose. This was years of pent-up racial hostilities and rage unleashed. This was a modern-day lynching, but there was a bat instead of a rope.”

On June 28, 1984, the jury found Nitz not guilty on both counts. Ebens was acquitted on the first count but found guilty on the second count of conspiracy. He was sentenced to 25 years in prison. The verdict was overturned on appeal nearly two years later.

The Department of Justice announced a retrial in September of 1986. Judge Anna Diggs Taylor who presided over the first trial and sentenced Ebens to 25 years for violating Vincent Chin’s civil rights ruled that because of publicity that Ebens would not receive a fair trial in Detroit. The case was moved to Cincinnati.

A jury – mostly white, male and blue-collar like Ebens, according to CNN – found him not guilty. He burst into tears as the verdict was read, Yoo writes.

“We said all along this case was a frame-up,” Eaman said. “This was never a civil rights case, and he got a fair trial.”

Lily Chin was heartbroken.

“My life is over,” she told the press. “Vincent’s soul will never rest.”

In March of 1987, Ebens was ordered to pay $1.5 million in settlement of a wrongful death lawsuit. He was supposed to pay $200 a month or 25 percent of his net income. The Chin estate has never collected any money, and the amount now exceeds $8 million because of interest, according to NBC News.

Oxygen.com was unable to reach Ebens, but he apologized for the murder saying he would take back that night, if he could, in an interview with journalist Emil Guillermo in 2012.

“It’s absolutely true, I’m sorry it happened and if there’s any way to undo it, I’d do it,” he told Guillermo. “Nobody feels good about somebody’s life being taken, okay? You just never get over it. … Anybody who hurts somebody else, if you’re a human being, you’re sorry, you know.”

He later added: “It should never have happened, and it had nothing to do with the auto industry or Asians or anything else. Never did, never will. I could have cared less about that. That’s the biggest fallacy of the whole thing.”

Lily Chin moved to San Francisco and then to China. She returned to Michigan for cancer treatments in 2001. She died in 2002, 20 years after her son.

“He became a martyr and she the crusader and emotional center for a budding movement,” the Los Angeles Times wrote in an article about Lily Chin’s death.

Vincent’s case was in the press once again when six women of Asian descent were gun downed in the Atlanta area last year. Crimes against Asian Americans rose more than 300 percent in 2021, according to the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism.

“I’ve been telling people that it’s going to get a lot worse before it gets better,” Shimoura said. "This wave has been ramped up. It will be a political issue in the fall and when the presidential election comes up in 2024. The pandemic isn’t going away. They are all basically feeding into the whole narrative about Anti-Asian hate.”

“Ironically, I actually do think that it’s good that history repeats itself because every time it repeats itself, so does the protests movements,” Yoo told Oxygen.com. “So, there’s a new generation of young people realizing we can’t stand for this.”

Next month, events are scheduled in Detroit to observe the 40th anniversary of Vincent’s death.

“The legacy of Vincent Chin is that it galvanized the Asian American community, so that justice could be better served in the future,” John Yang, president and executive director of Asians Advancing Justice told Oxygen.com. “There is from this tragedy a positive, which is the growing strength of a community."