Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, breaking news, sweepstakes, and more!

'They Got A Knife to My Throat Right Now': Alabama Family Says They Were Extorted By Prison Inmates Using Smartphones

Ryan Rust, whose family claims he was the victim of a vicious cell phone extortion scheme, was found dead and hanging from a belt inside his Alabama prison cell in 2018.

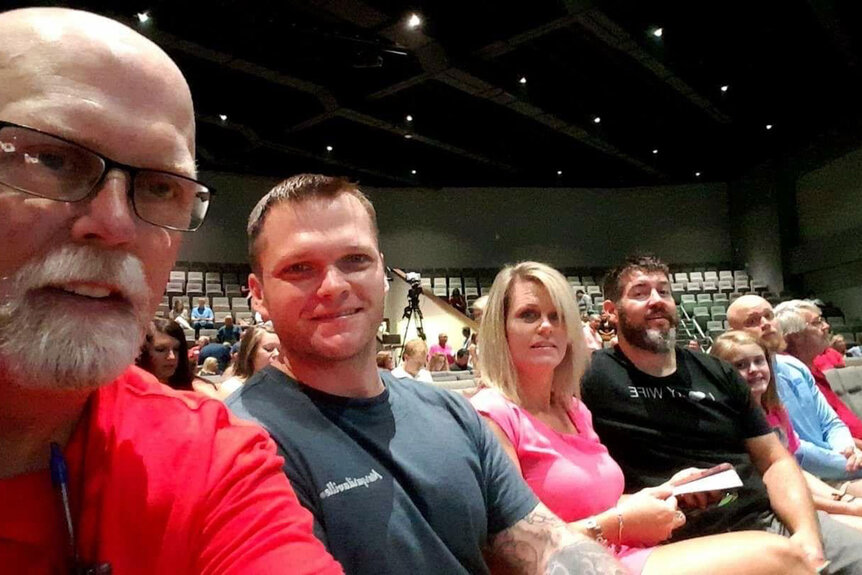

Jeff Rust decided to arm himself shortly after the threatening calls began.

In 2018, Jeff, a 64-year-old Alabama towboat captain, was receiving multiple calls or text messages a day from inmates locked up behind prison walls hundreds of miles away.

Prisoners, using smuggled cell phones, warned Jeff they’d seriously injure — or kill — his son Ryan, who serving time at a state prison in southern Alabama.

“We would get phone calls and text messages, every day, sometimes two or three times a day,” Jeff told Oxygen.com.

Sometimes the messages would come from Ryan himself, who also had access to a smartphone. His son’s pleas were always the same.

“‘Dad, I need you to send money, otherwise I’m going to be hurt,’” Jeff recalled.

Ryan, who had been arrested earlier that year on a parole violation stemming from a past statutory rape charge, was desperate, his father said. He had been stabbed twice and slashed with a box cutter on a separate occasion, over what his father suspects was payback for an unsettled debt.

One day, a message demanding cash was sent to Jeff's phone. It included a picture of his house in Daphne, Alabama.

“They sent a picture of my dad’s house to me and to my dad and said that the house was going to burn down that night if $2,000 wasn’t sent,” Harmony Rust-Bodke, Ryan’s sister, told Oxygen.com. “What do you do? You don’t want anything to happen to your family.”

Jeff has since purchased an AR-15 semi-automatic rifle — including “1,000 rounds” of ammunition. He also installed a security fence and surveillance systems. Before the Alabama father steps foot outside each day, a guard dog does a perimeter check of his Daphne home, he said.

“With the cell phones, they can reach outside that prison to anybody at any time,” Jeff said. “My son, he wasn’t an angel, but he wasn’t a murderer, he wasn’t a violent inmate. He had a drug problem, on and off … that was no secret. And drugs in jail, they cost money.”

His daughter, Harmony, who also received frequent electronic threats armed herself as well.

“My daughter and I both have concealed carry permits,” he said. “We both carry, we don’t leave the house without sidearms.”

Ryan Rust, who had run his own granite installation company, loved motorcycles, varsity football, and knew how to make "everyone laugh," his family said. They described him as "kind-hearted" and a "hard worker. However, he battled drug addiction for much of his adult life — and was no stranger to the Alabama correctional system.

In 2015, Rust was dealt a three-year prison sentence on theft charges. He was released the following year. In January 2018, however, the 33-year-old was extradited from Arizona back to his home state, where he found himself back behind bars after violating parole conditions.

While incarcerated at Bullock Correctional Facility, Rust lost his commissary privileges. He was prohibited access to simple luxuries like toothpaste, deodorant, and coffee. Ryan then allegedly turned to other inmates, who sold him such goods at inflated prices. And thus began the cycle of debt — and extortion, according to Jeff.

To cover the cost, Ryan turned to his father, who began sending his son funds. His family suspected the money they sent was also used to facilitate a drug habit. Fellow prisoners, however, quickly took notice — and the arrangement gradually morphed into a full-blown racket.

Soon, Jeff said he was receiving phone calls and texts from inmates claiming his son owed them money. At first, he began wiring them small amounts. He’d send $30 here and maybe $40, or $50 there, he said. But the amounts gradually skyrocketed into the hundreds — and eventually exceeded $1,000.

In 2018 alone, Jeff estimated he sent upward of $21,000 to a rotating cast of prisoners in order to ensure his son wasn’t gravely harmed, or worse, killed.

Once, Jeff received a phone call indicating his son would have boiling oil poured over his body if he didn’t pay up.

“They were going to put baby oil in the microwave and get it up to a boiling temperature and then throw it on him,” Jeff said.

Another time, the Alabama father received a call from his son, advising him he was being held at knifepoint.

“‘They got a knife to my throat right now,’” he recalled his son telling him.

“It got so bad, my brother would call in the middle of night to tell the prison to put him in protective custody or lock up so he wouldn’t get killed because he was getting threatened all the time,” Harmony said.

The family used mobile apps like MoneyGram, Western Union, and Cash App to facilitate the transfers. The funds, they said, were then often deposited into the bank accounts of prisoners’ wives, girlfriends, or other associates, who then transferred them the money, or kept it for themselves. Once, the family even mailed a cell phone to a woman in Missouri. The family suspects the men who men behind the supposed extortion

The Rusts claimed to have reached out to corrections officials on multiple occasions to flag the alleged cell phone extortion, as well as Ryan's situation, but said their complaints went unaddressed.

By late 2018, Ryan was living a tormented existence. After facing the prospect of daily beatings and death threats, he sent a list of prisoner names to his father, who he identified as the inmates extorting him and suspected might one day kill him if he didn't pay up.

“If anything happens to me make sure you remember that list of names I gave you,” Ryan texted his father on Nov. 5, according to screenshots of the conversation obtained by Oxygen.com.

Naming specific individuals, Ryan added, they’re “seriously trying to have this hit followed through.”

On Nov. 30, Jeff wrote his son, “Best gift you could ever get me is to come home to me safe and sound.”

Ryan responded: “I’ll try pops. I got my ear cut in half [in] a fight guy cut me with a blade.”

After remortgaging his home to cover the alleged debts incurred by his son, the Alabama father was nearing financial crisis and was determined to practice tough love. He said he later sent two separate — and final — $1,500 installments to a prisoner associate of his son’s.

“I told [them] to leave Ryan the hell alone,” Jeff said.

Afterward, the Rusts visited Ryan at Fountain Correctional Facility near Atmore, Alabama in mid-December. He had two black eyes. It was the last time the family saw him. Days later, Ryan tried escaping his prison unit out of fear for his safety, according to his family. His attempt failed and he was later transferred to a William C. Holman Correctional Facility.

On Dec. 21, 2018, Ryan was found hanging by a belt in his cell. His death was ultimately ruled a suicide, according to corrections officials. He was 33.

“Upon completing our investigation into the details surrounding his death, and upon receipt of full autopsy results, his death was ruled a suicide by hanging,” Samantha Rose, a spokesperson for the Alabama Department Of Corrections, said in a statement sent to Oxygen.com.

No “foul play” was suspected, officials said. However, nearly two years later, the Rust family still has their doubts.

“We suspect it was other than suicide,” Jeff said.

The family, too, is still wary they could be targeted at any time.

“I carry a gun with me at all times,” Harmony said. “These guys friended me on Facebook. They know what I look like. They know what my kids look like. They know the name of my business. I live in a small town. It’s not hard to find me. I keep protection on me at all times.”

Before mobile phones, inmates used pay phones to carry out such schemes, experts said. But that’s changed. Cell phone extortion is now a “common practice” in many U.S. prisons.

“Unfortunately it’s something we hear about with some regularity,” Sarah Geraghty, a senior attorney with the Southern Center for Human Rights, told Oxygen.com. “A family member will get a call from a loved one and they’ll get a threat that something terrible will happen … and the threat is your loved one will be injured or your loved one will be killed."

The Georgia attorney estimated there are tens of thousands of smuggled cell phones stashed in every imaginable nook and cranny of prisons across the U.S. In many cases, she said, corrections officers and prison workers are responsible for the illicit flow of smartphones.

“It’s beyond debate that they come from a number of sources,” Geraghty explained. “They come from officers, they come from other prison staff workers like food delivery people, in some instances they come from incarcerated family members or loved ones, and in some cases they are thrown over a perimeter fence.”

Last month, guards at a prison in Clayton, Alabama seized a basketball containing 16 mobile phones. It had been tossed over a prison fence “under the cover of darkness,” officials said. Drones have also emerged as a popular mode to covertly deliver prison smartphones. Other times, animal carcasses, like dead tomcats, are used as vessels to bootleg cell phones over prison walls.

Prison experts and corrections officials alike agreed it’s nearly impossible to stem the flow of such devices. Frequent sweeps, K9 dogs, infrared cameras, and other electronic equipment used to detect cell phones are ineffective, particularly in understaffed facilities where inmates can easily exploit security oversights.

“The ADOC works very hard to eliminate contraband across all its facilities,” Rose, the state correctional spokesperson, added. “We organize and run large-scale raids to sweep facilities clean to try to ‘reset them.’ We recognize that there likely is a significant number of phones that go undiscovered during sweeps due to the nature of our dilapidated facilities.”

Rose acknowledged prison staff are “complicit in these schemes,” noting the department “actively” works to eliminate “persisting corruption.”

“I liken bringing in a cell phone [into prison] to that of bringing in a gun,” Terry Pelz, a former Texas prison warden and adjunct instructor of criminal justice at the University of Houston Downtown, told Oxygen.com.

Pelz explained it’s a felony offense to smuggle cell phones into Texas prisons. Yet, trafficking pirated cell phones behind bars is an often violent and “lucrative business," he said.

“Most [smartphones] are used to further criminal enterprises by prison gangs, order hits on the outside,” he explained. “Inmates also use them to extort from other inmates by threatening their families … When you're short staffed, as most prisons are, more contraband gets in.”

To curb the incursion of smart devices, the Justice Department has long-proposed the strategy of blocking cell signals on cell blocks using signal jammers. Pelz, however, noted such disruptive technology poses safety risks, too, and violates FCC regulations.

“The problem before with the FCC is that jamming caused others in the adjacent areas of the free world to be affected,” Pelz said. “Congress was supposed to act on that. It just kind of went away.”

In 2019, the Cell Phone Jamming Reform Act, which would allow state and federal detention centers to operate jammers, was introduced in the U.S. Senate. The legislation hasn’t been passed.

Alabama corrections officials denied receiving any formal complaints from the Rust family regarding the alleged cell phone extortion, adding it “does not tolerate extortion of any kind.”

“We have confirmed that no instances of extortion were formally reported by inmate Ryan Rust or his family to the Alabama Department of Corrections,” a spokesperson for the department stated.

The Rust family, however, remains unconvinced.

Shortly before his death, Ryan had struck a plea deal that would have secured his release in the fall of 2019, his family said. He and his girlfriend had even picked out a home together, which they planned to move into following his release.

“I don’t believe that Ryan killed himself because he only had nine months or so to go before he was getting out,” his sister said. “He had everything planned. He had a lot to look forward to.”

Their suspicions were further provoked after being inundated by messages from a number of his fellow prisoners and prison staff — some who hinted Ryan’s death wasn’t a suicide.

Harmony, who owns a motorcycle performance shop, said she received several texts and Facebook messages from inmates who knew her brother following his death.

“A few of them contacted me and told me that ‘your brother didn’t kill himself,”’ Harmony said. “I had some people text me directly to my phone and wouldn't give me who they were, and course it was a number I couldn’t see who it belonged to and tell me, ‘So and so a guard here, killed your brother.’”

Earlier this year, the Rust family, along with relatives of three other inmates who died by suicide while incarcerated, filed a class action lawsuit against the Alabama Department of Corrections. A correctional spokesperson declined to comment on the pending case.

The Rusts also plan to file a wrongful death civil suit against the state.

“It’s terrible,” Jeff said. “Sometimes I’m up all night. I want answers. I want to know who’s responsible, I want to know the damn truth. I want justice for my son. It won’t bring him back but maybe it will save somebody else’s son, or somebody else’s father.”