Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, breaking news, sweepstakes, and more!

Charles Augustus Lindbergh, Jr.: The True Story of The Lindbergh Baby Kidnapping

Charles Augustus Lindbergh, Jr.'s kidnapping shocked the nation during the Great Depression and fueled a media frenzy that would force the family into hiding.

The Lindbergh baby case has often been referred to as the “crime of the century,” sparking conspiracy theories in the years that followed.

The saga began in earnest when Charles Lindbergh — the first aviator to fly non-stop from New York City to Paris — and his wife, Anne Morrow, welcomed their first son, Charles Augustus Lindbergh, Jr., on June 22, 1930. The arrival of their first child came shortly after the senior Lindbergh had completed his transatlantic flight, which earned him multiple awards, including Time magazine's Man of the Year and a Medal of Honor.

The Lindberghs were once again in the spotlight when their 20-month-old was kidnapped around 9 p.m. on March 1, 1932. Around 10 p.m., the baby’s nurse, Betty Gow, discovered he was missing from his nursery on the second floor of the Lindberghs’ New Jersey home. A ransom note demanding $50,000 was found on the nursery window sill. There were traces of mud on the floor and a ladder was found outside the window, which had seemingly been broken during the ascent or descent into the nursery. No fingerprints were left at the scene.

RELATED: How Amber Hagerman's Loved Ones Found Healing In Creating The Amber Alert

A second note was received by Colonel Lindbergh on March 6, 1932. The note, postmarked from Brooklyn, increased the demand to $70,000. John F. Condon, a retired school principal, wrote a letter to the Bronx Home News offering $1,000 if the kidnapper turned the baby over to a Catholic priest.

Another note that claimed to be from the kidnapper, also postmarked from Brooklyn, stated that Condon should be the intermediary between him and the Lindberghs. Colonel Lindbergh approved of the request, assuming that the notes were genuine. He gave Condon $70,000 in cash as ransom, and Condon began discussing payment logistics through newspaper columns, using the code name “Jafsie.” Soon after Condon received a message in person, delivered by a taxicab driver, who claimed he had received it from an unidentified stranger. The note stated that another note would be found beneath a stone at a vacant stand, 100 feet from a subway station exit. Sure enough, there was a note under the stone, which ordered Condon to meet a man who called himself “John,” at a cemetery. Condon met with “John” who provided the baby’s sleeping suit as a way to prove he had the child. The suit was delivered to Colonel Lindbergh, who confirmed it belonged to his son.

When Condon gave “John” the money at a later meeting, “John” handed instructions to find the kidnapped child. It stated that he could be found on a boat named “Nellie” near Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts. Several searches for the baby near Martha’s Vineyard were unsuccessful.

While the meetings between “John” and Condon were going on, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover stated that the organization would be involved in finding those responsible for the crime. Previously, kidnapping was considered only a local crime— though it would later become a federal crime when congress passed legislation informally dubbed the "Lindbergh Law."

On May 12, 1932, two months after the Lindbergh baby went missing, a baby’s body was found four and a half miles from the Lindbergh home by a truck driver. The head of the partly buried, decomposed baby was crushed. There was a hole in the skull and some of the body parts were missing. A Coroner’s examination showed that the child had been dead for about two months, and that the child died after a blow to the head. It was later positively identified as Charles Lindbergh, Jr. Authorities theorized that the kidnapper may have accidentally dropped the boy while climbing down the ladder.

Two years later, in September 1934, a man in a Dodge sedan pulled up to the gasoline pumps at a service station in upper Manhattan. To pay for his gas, the driver reached into his inside coat pocket retrieved a gold certificate, which had been pulled from circulation over a year earlier.

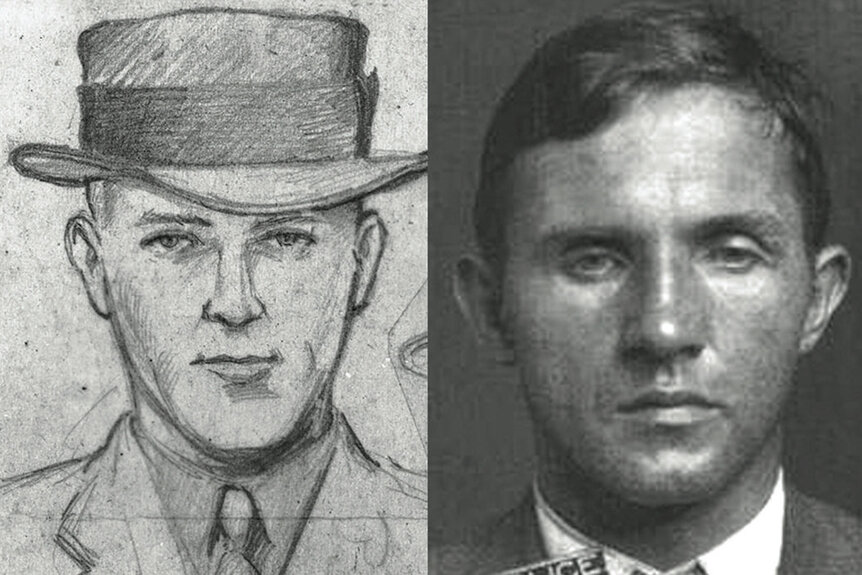

The attendant thought it was suspicious and figured he could be a counterfeiter, so when the driver left, he jotted down the car’s license plate number. After the service station deposited the certificate, a bank teller was also alarmed. The bill was connected to the $70,000 ransom paid to the kidnapper of Charles Lindbergh Jr. The bank notified federal investigators, who tracked the bill down to Bruno Richard Hauptmann, a carpenter who lived in the Bronx. Hauptmann was arrested the next day. Police found $13,750 of the ransom money hidden inside a dirty oil can, which was stuffed in a package inside a wall and buried beneath the garage floor in a jar inside his garage. Handwriting experts claimed his handwriting matched that of the ransom notes.

Hauptmann denied having anything to do with the missing baby. He instead claimed he had been given the money by a deceased business partner and that he is merely scared of inflation. His neighbors said they noticed that Hauptmann suddenly stopped working in 1932, which Hauptmann chalked up to Wall Street money. Mind you, this was during the Great Depression.

A sensational trial followed, and Hauptmann was convicted of kidnapping and murder in 1935. He was executed by electrocution on April 3, 1936.

It was around this time that Lindbergh, Morrow and their second-born son, Jon, secretly moved to Europe to escape the unrelenting media frenzy surrounding the case. They lived in England and France for nearly three years before returning to New York in April 1939.