Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, breaking news, sweepstakes, and more!

What Is MOVE And How Did Their Years-Long Battle With Philadelphia Police End In Tragedy?

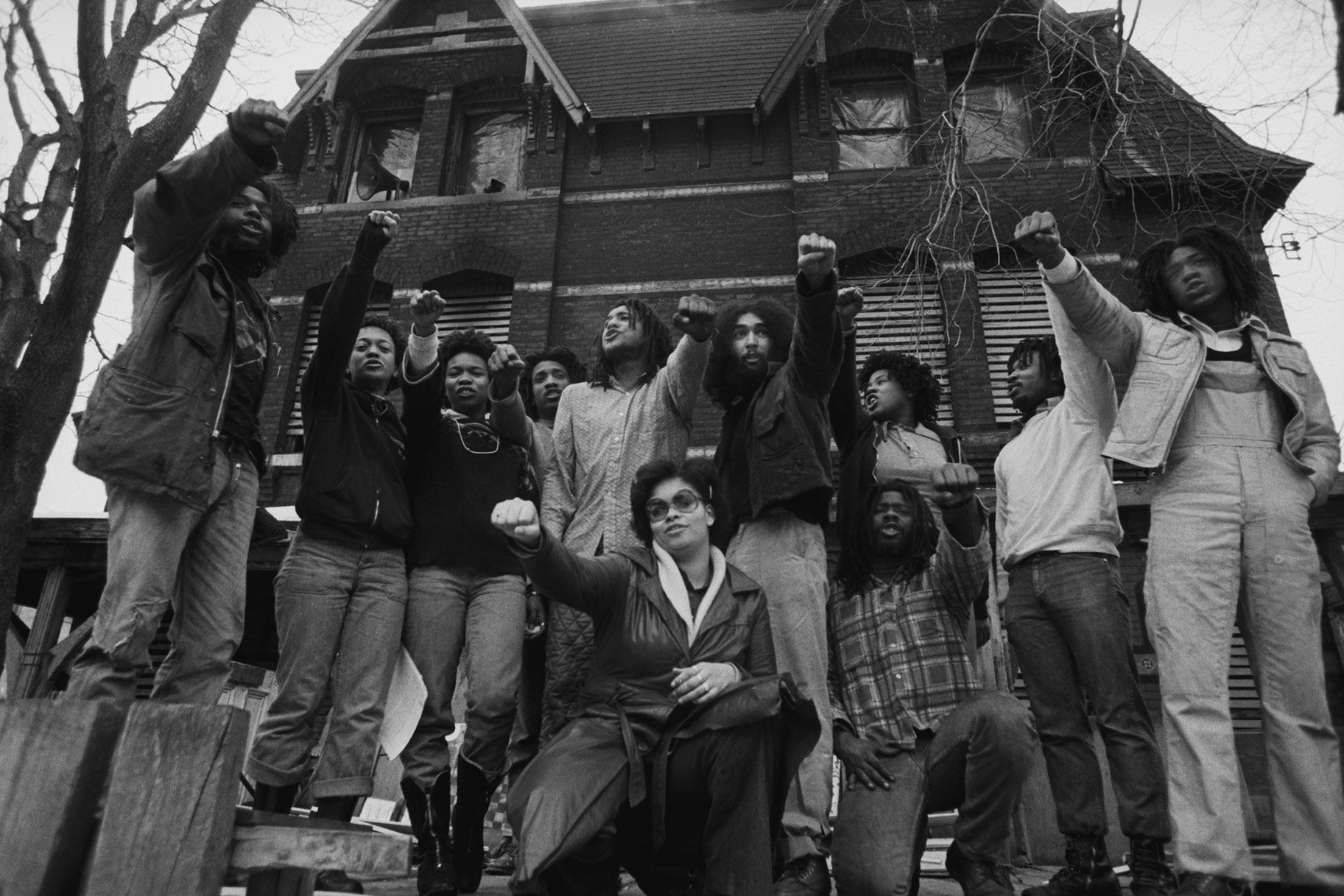

MOVE, a revoluntionary "back-to-nature" group formed in the 1970s, had not one but two shocking and deadly encounters with Philadelphia police.

Racial injustice has taken center stage in 2020—but a new HBO documentary highlights another raciallycharged battle between Philadelphia police and a Black revolutionary, back-to-nature group that began nearly 50 years ago.

The years long-battle between the group MOVE and authorities left one police officer dead and sent nine of the group’s members, known as the MOVE 9, to prison for third-degree murder after a 1978 attempt to evict the group from their Philadelphia home. It culminated nearly seven years later, in 1985, with in a city-sanctioned bombing that left 11 dead, including five children, and burned down 61 homes in another aggressive attempt by officials to evict the group from a new residence, according to Vox.

The documentary “40 Years A Prisoner,” which debuted on HBO Tuesday, focuses on the first deadly altercation in 1978 and Mike Africa Jr.’s attempts to free his parents from prison decades after they were convicted of a murder they said they didn’t commit.

But the violence that erupted on Aug. 8, 1978 as local media and residents in the Powelton Village neighborhood of Philadelphia looked on was only a pre-cursor to the deadly altercation in 1985, which has been described by Philadelphia Council member Jamie Gauthier as “one of the worst acts that a government has committed against its own people,” according to The Philadelphia Tribune.

What Is MOVE?

The MOVE organization describes itself as a “family of strong, serious, deeply committed revolutionaries founded by a wise, perceptive, strategically-minded Black man named John Africa,” according to the group’s website.

John Africa, a veteran of the Korean war who had been born as Vincent Lopez Leaphart, started the group in the early 1970s. The group’s philosophies were an unusual mix of flower power—protesting against the enslavement of animals, eating raw food and adopting a communal living style—and Black power, The Guardian reports.

“We exposed the crimes of government officials on every level,” member Janine Africa told the outlet from prison in 2018. “We demonstrated against puppy mills, zoos, circuses, any form of enslavement of animals. We demonstrated against Three Mile Island [nuclear power plant] and industrial pollution. We demonstrated against police brutality. And we did so uncompromisingly. Slavery never ended, it was just disguised.”

Members of the group—which still exists today—all take on the last name “Africa” to show they are a “unified” family and to pay reverence to their founder and their ancestral roots.

The political and religious organization—often described as a “back-to-nature” movement—adopted principles that were anti-government, anti-technology, and anti-corporation.

“We believe in Natural Law, the government of self,” the group’s website states. “Man-made laws are not really laws, because they don’t apply equally to everyone and they contain exceptions and loopholes.”

In the 1970s, group members lived together in a home in Powelton Village, collectively caring for their children. They also looked after stray dogs in the neighborhood.

But the group’s lifestyle — they used bull horns to loudly profess their beliefs and erected wood platforms and fences around their property in the urban neighborhood, according to “40 Years A Prisoner” — didn’t sit well with some of their neighbors.

The conflict escalated to a dispute between MOVE and the city that would ultimately end with deadly consequences.

A Life Is Lost

MOVE members say the dispute between the group and police began on March 28, 1976 after MOVE members went to pick up some of their fellow members from jail.

“Then when we got back, there was a big celebration and not too long after that we was moved on by a whole bunch of cops,” Mo Africa said in the documentary. “Cops were swinging their night sticks so hard on people that they broke them in half.”

Louise Africa said during the altercation officers knocked Janine Africa to the ground “crushing her baby’s skull.”

The 3-week-old baby she had named Life died later that day in her arms, according to The Guardian.

“I don’t like thinking about the night Life was killed,” Janine wrote the outlet years later, saying the memories were too painful to recall.

The baby had been born at the house and didn’t have a birth certificate. MOVE members said they called council members and members of the media out to view the baby’s body but no autopsy was ever conducted to confirm the cause of the death.

Investigative journalist Linn Washington Jr. said in the documentary that the city denied causing the baby’s death but “those denials didn’t have too much weight because they were also denying the gross brutality that was going on by the police.”

At the time, there were frequent reports of shootings of unarmed individuals and police brutality under the city’s leadership by Mayor Frank Rizzo. According an investigation by The Philadelphia Inquirer in 1977, 80 out of 433 homicide cases over a three-year period involved illegal interrogation and investigation methods.

In 1979, a Public Interest Law Center study would find that nearly half of police shootings violated state law. Between 1970 and 1978, 75 people had been shot even though they were not charged with a crime and were “unarmed and were retreating from an officer.” In 1978, two-thirds of the people killed by police that year were either Black or Hispanic.

Lengthy Stand-Off

The baby’s death in 1976 was the spark that ignited the long-standing feud between MOVE, city officials and police. As tensions rose, MOVE members began using a bullhorn to profess their often expletive-laced views into the streets and were armed with guns. They built fences and barricades around the Powelton Village property and boarded up windows of the house.

“There were no longer going to be any more beatings, any brutality without us defending ourself,” Louise Africa said in “40 Weeks a Prisoner.”

City officials deemed the group an “authoritarian, violence-threatening cult,” and said the group often used threats of violence and intimidation against their neighbors, according to The New York Times.

“They were just vulgar people and if you got in front of them, they’d just curse you out,” Tom Hesson, a Philadelphia Police officer who was shot during the 1978 incident said in the documentary.

Some neighbors wanted to see the group evicted, but MOVE continued to stay put, standing outside their home on a platform, dressed in fatigues and carrying rifles.

By 1978, Rizzo ordered a police blockade that would prevent any food or water from getting to the home for 56 days straight.

“You are dealing with criminal, barbarians, you are safer in the jungle!” Rizzo once described the MOVE radicals, according to The Guardian.

As the standoff continued, MOVE demanded that some of its members be released from jail, while the city demanded members clean up the house or move, according to the documentary.

“They kept talking past each other and MOVE never did anything to clean up the house that I was aware of,” Joel Todd, a former MOVE lawyer, said in the documentary.

For a period of 90 days in the summer of 1978, it seemed like a truce might be reached after MOVE agreed to hand over their mostly inoperable weapons and the city agreed to release several MOVE members from city jails, NPR reported.

Washington said in the documentary that the agreement had also allegedly included an understanding that MOVE would be allowed to stay in the house until they were able to move out, yet Rizzo would later insist that group needed to leave the home by August 1, 1978.

“That really wasn’t a clear understanding from everybody on that Aug. 1 date of getting out,” Washington said.

Shooting Erupts

The conflict would reach a breaking point on the morning of Aug. 8, 1978. Around 6 a.m. heavily-armed police doused the home with water, using a water cannon that shot into the basement where MOVE members—including 12 adults, 11 children and 48 dogs—had sought refuge, The Guardian reports.

The water began filling the basement, reaching Louise Africa’s chest. She recalled in the documentary having to hold her son above her chest to keep him from drowning in the water.

A short time later — around 8:15 a.m. — a shot rang out, setting off a hail of gunfire that killed officer James Rump. Another 18 police officers and firefighters were hurt during the incident, according to The Philadelphia Inquirer.

MOVE maintained that Rump was killed as a result of “friendly fire,” but authorities argued that MOVE members had fired the fatal shot.

Nine members of the group—including Mike Africa Jr.’s parents Debbie Africa and Mike Africa—were ultimately convicted of third-degree murder and sentenced to 30 to 100 years in prison for the killing. Rump had been killed by one bullet, but the nine members were collectively charged for the death, The Guardian reported in 2018.

After the shooting stopped, adults and children were taken from the basement. Delbert Africa, one of the members later convicted in the killing, emerged shirtless and unarmed with his hands out-stretched, but he was viciously beaten by three police officers.

“I’m unconscious, and that’s when one cop pulled me by the hair across the street, one cop started jumping on my head, one started kicking me in the ribs and beating me,” Delbert Africa would later tell The Philadelphia Inquirer.

The three cops were arrested and charged with beating Delbert Africa, but a judge would later throw the case out.

The same day that the siege was carried out, Rizzo ordered the MOVE headquarters to be destroyed.

Bombing That Shocked A City

The deadly siege wouldn’t end the conflict between MOVE and city officials. After their Powelton Village house was destroyed, the group relocated to a townhouse at 6221 Osage Ave.

But the group’s new neighbors also began to complain to the city, now under the direction of Mayor Wilson Goode, citing many of the same complaints that had angered the group’s earlier neighbors.

They complained that the group left trash around the home, got into conflicts with the neighbors and continued to use the bullhorn to blast profane political messages to those within earshot, Vox reports.

Goode gave the order to evict the group—but the conflict would result in unprecedented destruction.

On May 12, 1985, nearby residents were urged to leave their homes ahead of the anticipated stand-off between police and MOVE.

“The cops evacuated our block the night before,” Akhen Wilson, who had lived next door to MOVE told Vox. “A lot of families went to shelters or hotels. My dad took us to a condo he started renting that week, because my parents were through with the situation. We took stuff to stay overnight and left everything else in the house.”

The next day, on May 13, 1985, close to 500 police officers swarmed the block, armed with machine guns and SWAT gear, and armed with warrants for several members they believed were living at the home, according to NPR.

“Attention, MOVE … This is America,” Gregore Sambor, the police commissioner at the time allegedly yelled through a megaphone just after 5:30 a.m. “You have to abide by the laws of the United States.”

They were given 15 minutes to come out of the bunker they had built inside the home. But the members did not come out and instead began to fire at police, according to NPR.

Police retaliated, firing at least 10,000 rounds of ammunition at the compound over 90 minutes.

William Brown III, chair of the Special Investigation MOVE Commission, would later say that MOVE did not have any automatic weapons and only had a “couple of shotguns and a rifle” inside the house.

“Yet the police fired so many rounds of ammunition—at least 10,000—into that building during the day that they had to send up to the police headquarters to get more,” he said, according to Vox.

At 5:27 p.m. authorities dropped a bomb that police had made of plastic explosives on the roof of the rowhouse that started a fire, according to The New York Times.

“We felt the house shake, but it hadn’t occurred to us that they dropped a bomb,” Ramona Africa, the lone adult survivor, would later recall, according to Vox. “Pretty quickly, it got smokier and smokier. At first we thought it was tear gas, but then it got thicker.”

As the fire began to spread, police ordered the firefighters to let it burn. The fire ultimately destroyed 61 homes, leaving more than 250 residents homeless. Five children and six adults, including MOVE founder John Africa, were killed.

Only two people in the MOVE headquarters survived the bombing, Ramona Africa and a young 13-year-old boy Birdie Africa, who was later known as Michael Moses Ward.

A commission would later determine the bombing had been “reckless” and “ill-conceived” but no one was ever criminally charged for the attack.

Ramona Africa served seven years in prison for rioting and conspiracy for warrants out against her before the bombing took place.

Janine Africa and Delbert Africa—who were in prison for the 1978 altercation with police—both lost children in the blaze, according to The Guardian.

“The murder of my children, my family, will always affect me, but not in a bad way,” Janine told the outlet, also referencing the earlier death of her baby Life. “When I think about what this system has done to me and my family, it makes me even more committed to my belief.”

Making Amends

Earlier this year, the Philadelphia City Council unanimously passed a resolution to formally apologize for the bombing, The Philadelphia Tribune reports.

“This was one of the worst acts that a government has committed against its own people,” Council member Jamie Gauthier, who represents District 3, said. “I think that it’s more than the horrific incident. It’s about the decades and decades of division that have existed between police and community. If we had done the hard work of addressing that atrocity then, in some way, we may not be where we are [today].”

Goode, who said he was not personally involved in the decision to drop the bomb but was serving as the chief executive of the city, also apologized for his role in a British newspaper earlier this year, ABC News reports.

“There can never be an excuse for dropping an explosive from a helicopter on to a house with men, women, and children inside and then letting the fire burn,” he wrote.

Officials hope the public apologies help foster healing in the community.

“I’m hoping that we can work on reconciliation and healing ... I would like to see real conversation between the community and law enforcement,” Gauthier said. “I’d like to see law enforcement really listen to Black and brown people.”

All surviving MOVE members who were jailed for the 1978 incident are now out on parole.