Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, breaking news, sweepstakes, and more!

Are You Solving Crimes Or Losing Privacy? What To Know Before Uploading DNA To A Genetic Website

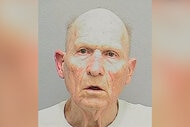

It allegedly caught the Golden State Killer — but many still fear there are ethical concerns around genetic genealogy sites.

Genetic genealogy has become a widespread fad over the last several years, with many uploading their DNA to websites to better understand their family history. But it's turned out to have another huge benefit: Genetic genealogy helped crack the decades-old cold case of the infamous Golden State Killer last year, and ever since it’s been leading to arrests in other unsolved murders, low and high profile alike. However, its rise in popularity has led to ethical concerns. How exactly how does it all work, and what do you need to know before you upload your own DNA to a genetic website? Will you be helping police arrest serial killers or are you just setting yourself up for a loss of privacy?

First, let’s begin with how the alleged Golden State Killer was captured, which marked the very first public arrest linked to genetic genealogy.

Police took a DNA sample found at one of the Golden State Killer's crime scenes, a sample which sat in storage for decades, and ran it through genealogy website GEDmatch. It matched with one of ex-cop Joseph DeAngelo's distant relatives. That doesn’t mean that police could narrow it down to him — not at first.

After the match was made, investigator and DNA expert Paul Holes and his team created about 25 family trees and combed through thousands of relatives from the 1800s until the present day, which eventually led them to DeAngelo. Then, police took a tissue from DeAngelo's trash and matched it with the crime scene DNA.

The arrest, hailed a success, also brought up concerns about privacy from activists and the general public alike.

So, is there a cause for concern?

Experts say there are several misconceptions about this new form of technology. They talked with Oxygen.com to set the record straight.

Only GEDMatch allows law enforcement usage.

Billy Jensen, a true crime investigative journalist, told Oxygen.com that if you upload your DNA to 23andMe or Ancestry.com, police cannot access it, at all.

“No you have to go one step further and do the GedMatch,” he explained.

GedMatch let its users know about its relationship with investigators.

“Gedmatch was clear about saying we are working with law enforcement,” Jensen told Oxygen.com.

It shouldn’t have been a surprise to those uploading their DNA.

Dr. Ellen McRae Greytak, director of bioinformatics at Parabon NanoLabs, a genetic profiling site that has worked with police before to run matches through Gedmatch, told Oxygen.com that the site updated its terms of service and put a notice on its front page so all the users had to accept the new use of terms when the company decided to allow law enforcement usage.

As for the other sites, like 23andMe, Greytak said that as long as everyone plays by the rules, they would also have to let their users know if they decide to change policies in the future.

“Everybody would have to be notified of that and they would have to once again choose whether or not to continue using the site in the same way as when GedMatch initially began allowing law enforcement usage.”

When you upload your DNA, even the police can’t “see” it.

Greytak explained that when one puts their data on GedMatch, neither police nor Parabon can see the DNA.

“We can’t actually see the DNA,” she said. “Your information that you put in GedMatch is not connected to health information.”

So, one’s raw genetic information isn’t visible. This should hopefully debunk fears that the DNA can be obtained and used by health insurance companies to search for pre-existing conditions.

Paul Holes recently told Oxygen.com at Death Becomes Us, a true crime festival in Washington, D.C., that “we can’t see anything about the genetics. All I see is you just share a certain percentage of your DNA with the guy I’m looking for, and once you get that number, it’s a number like 63.5 (percent shared match), it doesn’t tell me anything about that person, from an intrusive aspect. It’s very, very minimal.”

Law enforcement can only search for suspects for specific crimes.

Parbon said it's only allowed to use GedMatch to help law enforcement with certain cases. It can’t be something minor.

Greytak explained to Oxygen.com that they only get contacted by a law enforcement agency who has a case where it has DNA and it has not gotten any matches in the local or in the national DNA database. That means it’s not a known offender, and their DNA hasn’t matched any of the suspects that's been checked.

GedMatch only allows law enforcement to use its data to identify unidentified remains, and those remains do not have to be someone who is the victim of a crime. Or, when it comes to suspects, the crime must specifically be homicide or sexual assault.

You likely put up more personal info on social media anyway.

“What people put online, in their social media accounts is so much more intrusive and we use that as law enforcement,” Holes told Oxygen.com. “We go to people’s Facebook pages, we look at their social media as we’re doing our investigations. They are willing to really expose themselves on that front, and my fear is people will think we are in this investigative genealogy technique we are prying into their medical predispositions and we can’t. We just don’t have that access.”

Jensen noted that yes, people are paranoid that law enforcement, or others, ”might do something weird with your data.” However, he noted, “They have so much of your data already. If they wanted to screw with you, they’d be doing it right now.”

The whole process is more complicated than you think.

Even if the DNA sample has a match with a cousin, that doesn’t mean that police can find the culprit. They then need to build family trees.

“Then they have to narrow it down to somebody who was in the area at the time who could have done this,” Jensen explained. “Then they had to go and get the DNA from the person.”

Greytak cited a recent article which claimed 60 percent of people with European descent can be identified and theoretically implicated from a genealogy database.

“That article made a lot of assumptions,” she said. “Basically it’s made a leap from 60 percent of Europeans will have a third cousin or closer match in a database and it jumps directly from that to therefore 60 percent of people can be identified disregarding how much work and difficulties in going from a third cousin match in a database to an identity of an unknown person. That is a huge amount of work and if it were just a single third cousin, that may not be possible.”

She likened genetic genealogy to a puzzle. She told Oxygen.com that finding the genetic match within that database is only giving a few pieces of the puzzle.

“But putting that together and finding the other 95 percent of the pieces of the puzzle, that's all genetic genealogy research.”

Most importantly, it can save lives.

Jensen said he can understand why people would have trepidation about uploading their DNA, but he encourages people to do it, in order to fight crime. He said it's not just about finding killers.

"It’s saving lives, too," he said. "It’s saving the next victim."

Gina Pace contributed to this report.