Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, breaking news, sweepstakes, and more!

The Little-Known Story Of The Atlanta Ripper

The Atlanta Ripper targeted young female working-class Black victims in the early 1900s, often slashing their throats, as terror gripped the city.

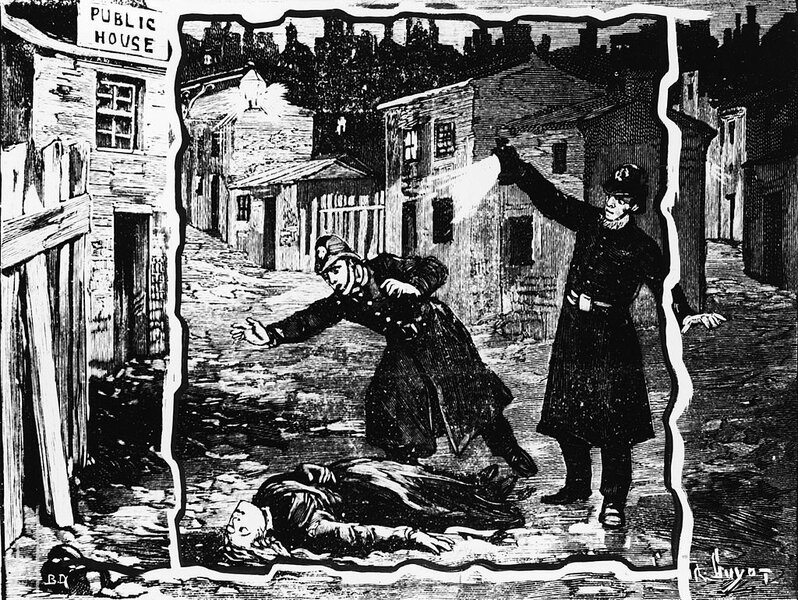

The chilling legacy of Jack the Ripper still lives on more than a century after the shocking London murders — but there was another “Ripper” in the United States who has been nearly forgotten.

Between 1911 and 1915 at least 20 Black women were brutally murdered in Atlanta — the setting of Oxygen's "Real Murders of Atlanta," airing Fridays at 9 p.m. — in a disturbingly similar manner. The victims had their throats slashed and many suffered significant head wounds, according to Atlanta News First.

The eerie similarities to Jack the Ripper prompted local media to refer to the unknown killer as “The Atlanta Ripper.”

RELATED: 'Real Murders Of Atlanta' Is Returning For Season 2

As the killings increased, there were several arrests, but no one was ever officially identified as the killer and the cases still remain unsolved today.

What is believed to be Atlanta’s first serial killer began his reign of terror during a time of high racial tension in the industrial city. Just years earlier, in 1906, a race riot broke out after local papers reported four unsubstantiated assaults on white women in the city, according to Atlanta News First.

As the news spread across the city, an angry mob of thousands of white men gathered downtown and began destroying Black-owned businesses, sending hundreds of Black men, women and children fleeing the city in fear.

Le Petit Journal of Paris reported at the time that “Black men and women were thrown from trolley-cars, assaulted with clubs and pelted with stones” during the riot, which left anywhere from 25 to 40 Black victims dead.

“At a time when the African American population in Atlanta was already nervous due to the growing racial tension that had gripped the city and led to the 1906 riots, the stories of the atrocities committed by the infamous Jack the Ripper in London were still fresh on everyone’s mind,” Jeffery Wells wrote in “The Atlanta Ripper: The Unsolved Case of the Gate City’s Most Infamous Murders.” “When the rash of murders broke out in Atlanta at the turn of the century, it was quite unnerving, and this nervousness was amplified by the fact that the murders in Atlanta shared more than a few similarities with those in London.”

Unlike Jack the Ripper, who targeted prostitutes in London’s East End, the Atlanta Ripper focused on Black or mixed-race working-class female victims.

It's difficult to pinpoint exactly when the first killings began but blogger Loria Johnston, who pieced the case together using old archived newspaper articles, wrote that the body of 23-year-old Maggie Brook was discovered on October 3, 1910. The young cook suffered a fractured skull.

Several months later, on January 22, 1911, the body of 35-year-old Rosa Trice was found not far from her house. Her skull had been crushed, her throat slashed and she had been stabbed in the jaw. Although her husband was arrested for the crime, he was later released due to a lack of evidence, The Atlanta Constitution reported at the time.

The next month, another unidentified Black woman, estimated to be about 25 years old, was found with her skull crushed in the woods by the West Point Belt Car Line.

The murders of Mary “Belle” Walker and Addie Watts soon followed in May and June of that year. The throats of both women had been slashed, Johnston wrote.

It was Watts’ death that sparked the idea that a serial killer targeting young Black women could be on the loose. The Atlanta Journal drew comparisons to the famed Jack the Ripper and questioned whether a “black butcher,” was running rampant in the southern city.

“The Atlanta press didn’t give a lot of attention to this in the early days of the murders,” Wells told Atlanta News First.

Many of the killings took place in the city’s old fourth ward, where there was limited lighting and a lack of street cars, providing the killer with a cover of darkness as he selected his victims.

“Many of them were domestic servants who worked in homes of white employers in the old fourth ward and the outlying areas,” Wells said. “As a matter of fact, one of the attacks happened really just down the street from one of the young lady’s employer’s home and the man... for whom she worked heard the ruckus and the commotion on the street, the screaming, ran outside to check and see what was going on, and was able to find the young lady but was not able to find the murderer, but did catch glimpse of the exit.”

The bodies were also often found near railroad tracks.

The death of 40-year-old Lena Sharpe on July 1, 1911 resulted in the first eye witness in the killings — although exactly what happened that day remains in dispute.

The Atlanta Constitution reported at the time that Sharpe’s daughter Emma Lou had grown concerned when her mother didn’t return from the market, noting that their neighbor Addie Watts was killed just weeks earlier, according to Johnston. Emma Lou went out to look for her mother and encountered a tall Black man who told her, “Don’t worry. I never hurt girls like you,” before stabbing her in the back and running off. Her mother’s body was later found nearby with her throat slashed.

RELATED: Follow The Trail Of 'Jack The Ripper' In Oxygen Book Club's February 2022 Book

In a differing account from The Atlanta Journal, the outlet reported that Lena and Emma Lou had been walking together when a Black man struck Lena in the head with a brick and then stabbed Emma Lou, who tried to flee but fainted. The killer slit Lena’s throat before returning to Emma Lou, who had regained consciousness and saw him standing over her with a knife. He ran off after he heard footsteps approaching.

In both instances, however, Emma Lou described the killer as a tall, slender Black man.

As the killings continued, Pastor Henry Hugh Proctor of the First Congregational Church in Atlanta called for Black leaders to join together to try to find the killer. They also urged police to hire Black detectives to investigate the crimes, believing they may be more likely to get Black residents to open up about what they knew, Johnston wrote.

When laundry worker Sadie Holley was found nearly decapitated with a large fracture to her head in the dirt on July 11, 1911 it was the first time the killings made the front page of The Atlanta Constitution, as hysteria among the community began to grow.

Police soon arrested Henry Huff — the last person to be seen arguing with Holley in a cab — after they found blood on his trousers and scratches on his arm. He was later indicted by a grand jury, but the killings continued. Huff was later found not guilty.

Mary Ann Duncan, 20, was found lying between railroad tracks with her throat slit on Aug. 31, 2011, and the bodies of Eva Florence, Minnie Wise and Mary Putnam were also found later that year.

When 18-year-old Mary Kates was found dead on April 8, 1912 with her throat slashed and her body mutilated with what appeared to be a surgical instrument, the Lexington, Kentucky paper The Leader described the killer as having “some anatomical knowledge,” Johnston reports.

As the months went by, more young Black women were killed.

Police arrested a man named Henry Brown in August of 1912 for Florence’s murder after his wife told police that he had come home wearing bloody clothing on several Saturdays that coincided with the killings. He was later acquitted after a witness testified that he had been beaten during his police interrogation until he confessed.

For more than ten years, until 1924, the bodies of slain Black women were discovered in the city, often with wounds to their heads or their throats slashed.

In 1917, the body of Laura Blackwell was found in her home. She had been killed with an axe and her throat slashed. Her clothes had been destroyed in a fire, Johnston wrote.

John Brown was arrested for the crime and was convicted in her death. Investigators believe he may have been responsible for the deaths of three other Black women who had been at least partially burned, but the killings didn’t end there.

It’s unclear exactly how many victims may have been killed by the suspected serial killer, but Wells believes they were at least 20 women.

Today, most believe that there was likely more than one killer at work over the years and some may have taken advantage of the media reports about the Atlanta Ripper to carry out their own acts of domestic violence.

“There were... some events that were attributed to what would become the Atlanta Ripper that ended up not being the work of the Atlanta Ripper and ended up being the work of disgruntled husbands and boyfriends,” Wells said.

Just exactly who the Atlanta Ripper was and how many women he killed still remains a mystery.

To learn about the modern murders afflicting the city of Atlanta, tune in to the second season of Oxygen's "Real Murders of Atlanta," airing Fridays at 9 p.m.