Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, breaking news, sweepstakes, and more!

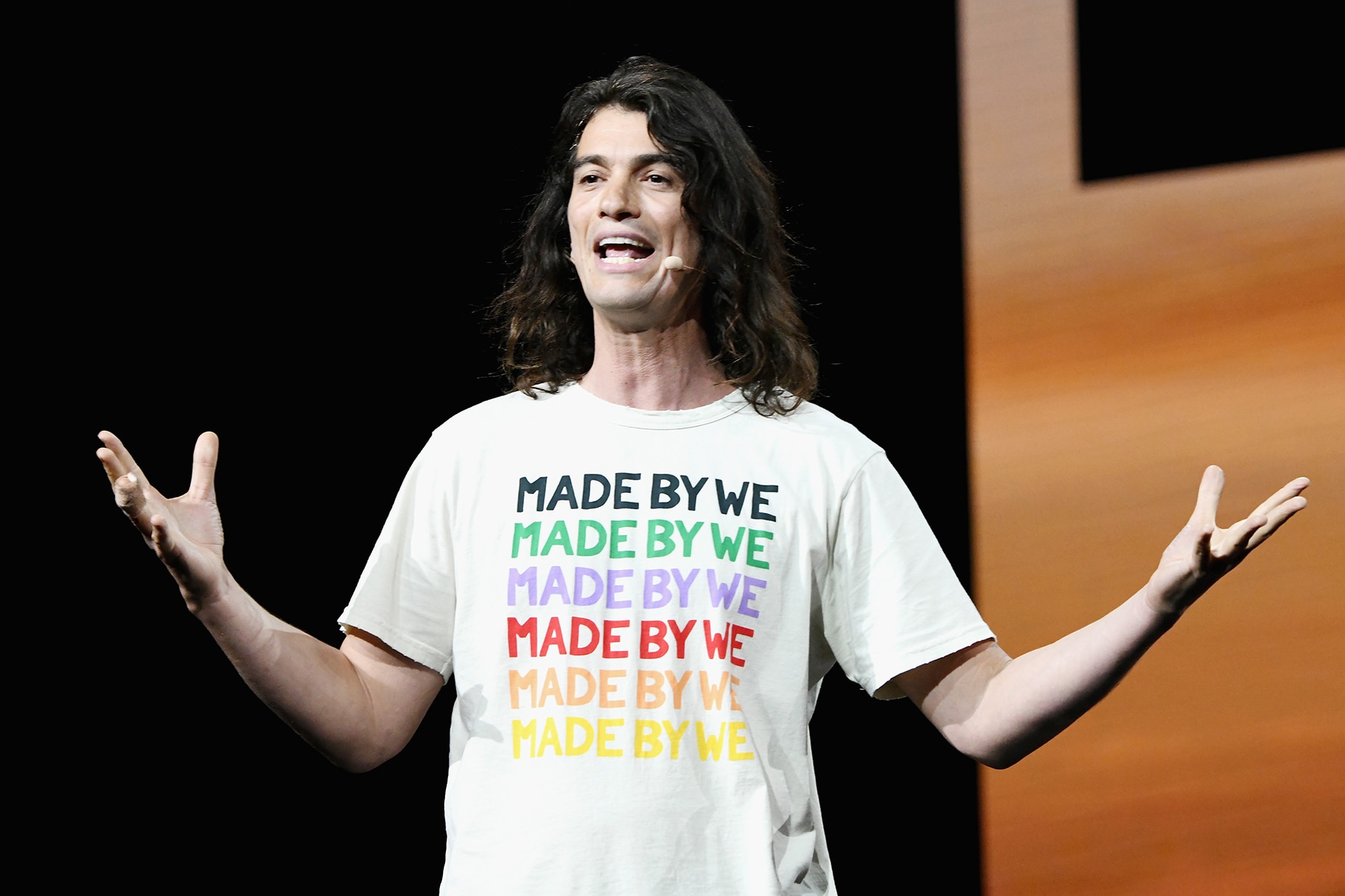

How WeWork Founder Walked Away With More Than $1 Billion While Many Employees Lost Their Jobs

“It was fun. It was really intense. It was around the clock, but people felt that they were all together building something huge,” author Maureen Farrell told CNBC's "American Greed" of the frenetic dynamic at WeWork under founder Adam Neumann.

WeWork promoted itself as an edgy co-working space complete with daily free beer, adult summer camps and a “work hard, play harder” atmosphere rivaling technology giants like Google and Facebook.

Founder Adam Neumann insisted that what made the company unique was its deeply entrenched sense of community among those who rented space at WeWork locations and raised $12 billion from venture capitalists who believed in Neumann’s optimistic vision.

But as the company was getting ready to go public, disturbing details about the company’s operations—including a history of negative profits, a bizarre succession plan involving Neumann's wife and reports that the sense of community had been greatly exaggerated—sent the company into a tailspin, according to CNBC's “American Greed,” which airs Wednesdays at 10 p.m. ET/PT.

While WeWork employees, who voiced complaints about long hours, required attendance at after-hour functions and no overtime pay, were left without jobs, Neumann himself cashed in and walked away from his post as CEO with more than a billion dollars.

Neumann—who grew up in a communal settlement in Israel known as a kibbutz—and business partner Miguel McKelvey got the idea for the hip co-working space while walking the streets of New York City, while trying to come up with the next great business idea.

The idea was simple: rent large loft space, subdivide it into smaller office areas with glass walls and attract start-ups to the location by providing a receptionist, communal area, coffee and other perks like ping pong tables, free beer and social events — things that the fledgling companies wouldn't be able to afford on their own.

Justin Zhen, cofounder of Thinknum Alternative Data, had been running his start-up from his kitchen when he moved into the coworking space.

“The common space kind of looked like a rainforest,” he recalled to “American Greed.” “They did a great job just selling that pitch right, if you don’t want to be in a boring old-fashioned office space, come to WeWork, we’re going to make your life great.”

Lisa Skye, WeWork’s second employee, remembers it felt like “this start of an era.” As the founding community manager, she was responsible for keeping the space running efficiently, whether it was managing sales, tours, billing or even IT.

“It was fun. It was really intense. It was around the clock, but people felt that they were all together building something huge,” said Maureen Farrell, the co-author of “The Cult of We.”

WeWork’s popularity quickly grew, catching the eye of venture capitalists, who were willing to put up seed money to see the business expand in the hopes of cashing in when the company made it big.

To secure their support, Neumann often gave interested investors tours of the space to give them a sense of the community feel—but those who worked behind the scenes said events were often staged or “very calculated” for those investor visits.

“A lot of folks talk about how Adam used to activate the space and what 'activating the space' meant was that when an investor would walk into the building, all of a sudden there’d be just this impromptu party,” Teddy Kramer, former WeWork employee told “American Greed.”

While some viewed the company as a real estate company, Neumann insisted it was a software business with an internal social network, described as the world’s first physical social network, that was transforming everyday work life and connecting businesses with other vendors and contractors.

“He was like the cocaine that Silicon Valley venture capitalists were just waiting to snort,” Charles Duhigg, reporter for The New Yorker Magazine, said of the company’s appeal to big name investors.

WeWork’s employees described the pace at the company’s various locations as frenetic, with long hours and low wages, but at first, those long hours seemed worth it because they believed they were getting in on the ground floor with a company primed to go public and make it big.

“I mean, the word rocket ship to success was actually used in my introduction meeting, that feeling of like you have Willy Wonka’s golden ticket. You are here at the right place and right time. You’re at the next Facebook or the next Google,” said former WeWork employee Tara Zoumer, adding that the company stressed everything staffers did was helping the community.

“They put the cult in culture was a common saying,” she said.

The company even hosted an adult summer camp in upstate New York — with top name musical artists like Florence and the Machine and Lin Manuel Miranda, and an endless supply of alcohol — which was mandatory for staff members to attend.

In marketing promotions, it appeared like a close-knit community, but there were cracks in the façade. Clients, like Zhen, reported that the community wasn’t “as close as what they were pitching it to be.”

He used his system of proprietary data analytics to assess the company’s highly touted social network and discovered that nearly 79% of WeWork members had never made a single post and that the top posters were actually employees of WeWork. When he published his data, he said he was asked to leave the co-working space by WeWork, who called his assessment inaccurate and incomplete.

Zoumer said she and other staff worked long days that often started at 8 a.m. and ended each day at 10 p.m., although she never was paid for any overtime.

“They used to say well, you get to stay at events, you get the opportunity of being here as if that’s compensation and it’s just not,” she said.

As investors continue to pour millions into the company, Neumann cashed out at least $700 million by selling off some of his stake or borrowing against some of his holdings, according to “American Greed.”

His investors seemed undeterred and in 2017 SoftBank Group founder Masayoshi Son, a Japanese billionaire, agreed on behalf of his firm to invest an initial $4.4 billion, one of the largest capital investments of all time, into the company. Softbank would ultimately pour more than $17 billion into WeWork, according to Bloomberg.

By 2018, the company had 425 locations with 400,000 clients—or members as they’re called—renting space at the facilities, but they hemorrhaging money.

It wasn’t until the company was planning to go public and released more details about their operations in August of 2019 that WeWork went into a tailspin.

Included in the documents prepared for federal regulators was a succession plan that gave Neumann’s wife Rebekah a key role in choosing his successor if he died or was permanently disabled. Personally, he had borrowed $740 million against WeWork’s stock and owned several of the buildings that WeWork was renting space from, making him the company’s landlord in some cases.

The financial reports also showed the company was losing billions each year, despite Neumann’s repeated claims that the company had been profitable.

While he wasn’t arrested or accused of any crimes, the WeWork board wanted Neumann removed and were willing to pay him an estimated $1.7 billion to step down.

Although Neumann raked in the cash, his employees got laid off and were forced to leave the company, which ultimately did go public in 2021.

“This system completely broke down. The guy who drove this company into the ground, he has walked away rich beyond belief. The people who empowered him, they made money, they’re doing just fine,” Duhigg said. “The people who got punished are the employees of WeWork, who just showed up, trying to do their job everyday.”

You can watch "American Greed," Wednesdays at 10 p.m. ET/PT on CNBC.