Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, breaking news, sweepstakes, and more!

The Ponzi Scheme Is Named After Fraudster Charles Ponzi; Here's What He Did

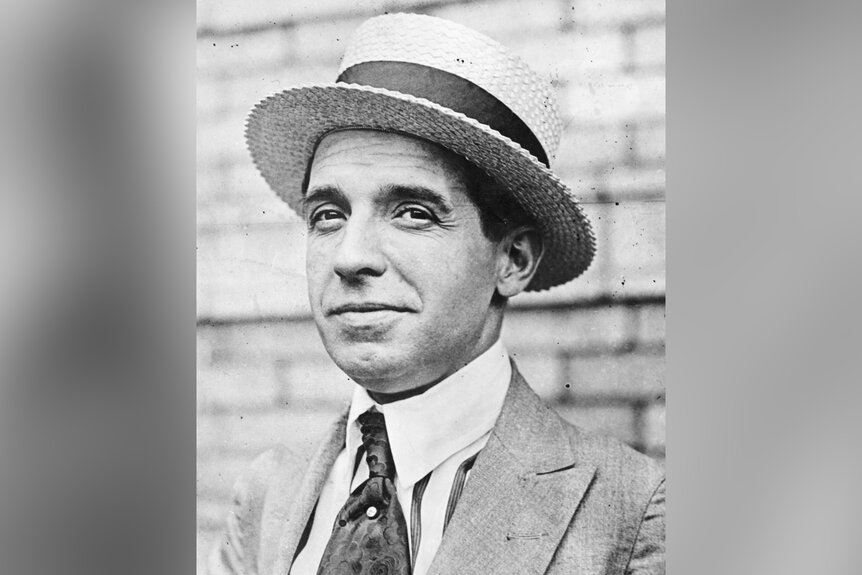

The investment scheme is named after Italian-born businessman and con artist Charles Ponzi, who swindled victims in the U.S. with a postage voucher scam.

The new docuseries, “Madoff: The Monster of Wall Street,” has placed disgraced financier Bernie Madoff back in the spotlight. The limited series, premiering Wednesday on Netflix, focuses on the fraudster behind a nearly $65 billion Ponzi scheme, one of the largest in Wall Street history.

The scandal made headlines across the globe for years, with coverage detailing Madoff's 2008 arrest, the thousands of investors he defrauded, his 2009 sentencing of 150 years in prison for securities fraud and other charges, and his ultimate death of natural causes in a federal prison in 2021.

The juicy story kept viewers intrigued and appalled at how he tricked investors with his Ponzi scheme — but what, exactly, is a Ponzi scheme, and who is it named for?

The investment scheme is named after Italian-born businessman and con artist Charles Ponzi, who swindled victims in the U.S. and Canada.

Ponzi arrived in the U.S. in 1903, according to CNN, taking several low-level jobs to make money, and eventually getting caught for stealing or ripping off patrons at most of them.

He then spent some time in Canada, landing in prison for a forged check. Later arriving back in the U.S., he was looking for way to make a lot of money fast, and turned to the postal system. Ponzi realized that letters sent to other countries at the time often included a voucher that could be traded in for postage back to the country where the mail was sent from, and that since exchange rates as well as stamp rates fluctuated, a profit could potentially be made, according to CNN.

It started out as a simple enough, and even legal, concept. Ponzi had the idea to buy postal coupons for a low price abroad, send them to America to trade them in for U.S. stamps that were worth more, and then sell those stamps. The con artist used his contacts in Italy to buy the postal reply coupons, and was coming out ahead financially, CNN reports.

But then things started to get dicey when he wanted more. Ponzi lined up investors, telling them they’d see returns of 50% within just days. Those he roped in would give him cash, and Ponzi would initially deliver big on the returns promise.

Word spread thanks to the initial investors who were being kept happy, and others from around the country were soon brought in to invest, while Ponzi was raking in millions and making a name for himself.

But not all was as it seemed. The cash being used to pay off the original investors was being funded by the newer ones, and many of the older investors were dumping more money into the operation, wanting to take advantage of what seemed like a great investment.

Suspicions began to arise and Clarence Barron, owner of Dow Jones & Company and the Wall Street Journal, began investigating Ponzi after realizing the postage operation could not have possibly been making as much money as the fraudster claimed it was.

Barron reasoned, according to CNN, that Ponzi would have had to have been dealing with 160 million coupons to make enough money to support his business model. But there were only 27,000 coupons that existed in circulation.

Barron’s findings ran in the Boston Post in July of 1920, with the reporting also detailing that Ponzi had told newspapers that he put his own money into traditional investments like stocks, bonds and real estate — which didn’t make sense considering their small returns, if Ponzi was indeed making 50 percent profits on the postage dealings.

Even after this front page news, investors still lined up to throw money into Ponzi’s alleged business, since they appeared to be making money on the practice. But things eventually started to go south when Ponzi tried to hire a publicist, William McMasters, who saw the fraudster for who he was and then publicly referred to him as a “financial idiot.”

The government was ultimately able to bring 86 charges against Ponzi for mail fraud, since he used the mail to tell those he duped how their investments were doing. He pleaded guilty to one of those charges to get a sentence of just five years. He served more than three years before being released and then being sentenced on state charges. But this didn’t stop him from going on to try to commit other crimes and facing more legal issues.

Ponzi died in 1949 in a hospital in Rio de Janeiro, but his name lives on. The term Ponzi scheme is now used to describe fraudulent operations in which money from recent investors is used to pay "profits" to earlier investors.

Those taking part are tricked into thinking they’re making money from a legal business model, without being told that any returns they’re making are actually coming from other investors. Thanks to the initial flow of money, by the time it takes investors to figure out what’s going on, it’s too late.

To find out how Madoff’s Ponzi scheme worked, check out “Madoff: The Monster of Wall Street,” debuting Wednesday on Netflix.