Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, breaking news, sweepstakes, and more!

What Was The Rainbow Coalition, As Seen In ‘Judas And The Black Messiah?’

The legacy of rainbow coalition politics has deep roots in Chicago, stretching from its origins in the city's Black Panther Party chapter to Barack Obama's historic presidential wins.

After Barack Obama’s 2008 election victory, it was said his historic win was the result of assembling a “rainbow coalition” of voters, which included Black, Hispanic, and women voters, as well as Americans from most income groups. The term at that point, which refers to a bloc of ideologically unrelated Americans, was mostly associated with the Rev. Jesse Jackson and his Chicago-based nonprofit, Rainbow/PUSH. But rainbow coalition politics has deeper historical roots in Chicago, with origins that can be traced to the city’s chapter of the Black Panther Party and its dynamic leader, Fred Hampton.

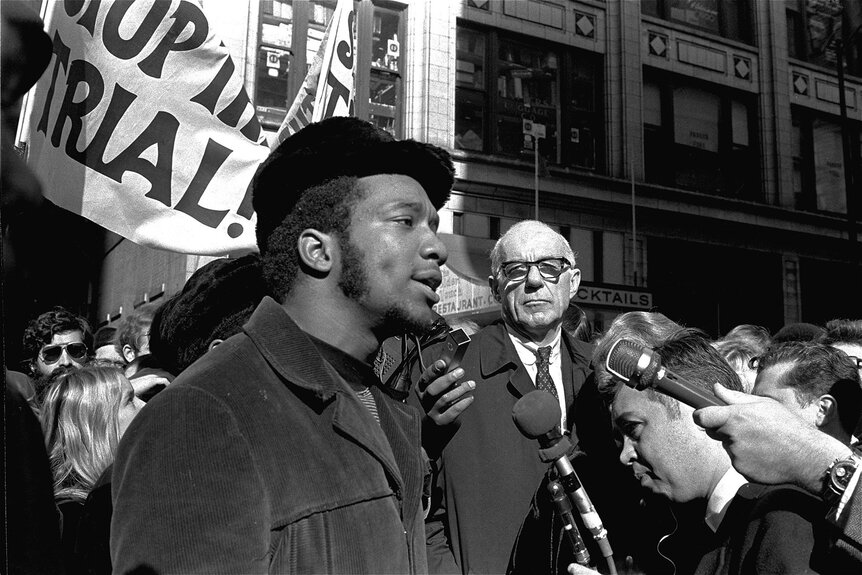

By 1969, Hampton had quickly risen from NAACP organizer to chairman of the Illinois chapter of the BPP. The charismatic 20-year-old set out that year to unify disparate community-based groups across Chicago, forming alliances across racial and ethnic lines. His effort is dramatized in “Judas and the Black Messiah,” which is available Friday in theaters and on HBO Max.

“He really could move people, whether it was law students, whether it was Hispanics, Puerto Ricans, Appalachians, and, of course, particularly people in the Black community, whether it was welfare members or gang members — Fred was very effective in organizing them and reaching them and mobilizing them,” attorney Jeff Haas, who represented the Black Panthers at the People's Law Office, told NPR in 2019.

As a leader in the BPP, Hampton organized rallies, strikes, taught daily political education classes, organized around community supervision of Chicago’s police, and began the BPP’s Free Breakfast for School Children program. But it was the overtures he made toward leaders of other marginalized political groups, including the Young Lords and the Young Patriots Organization, that cemented his legacy as a unifier for social justice.

Hampton met José Cha Cha Jiménez, the founder of the Young Lords, in February of 1969. A Puerto Rican and Latino street gang that morphed into a civil rights organization, the Young Lords fought against evictions of Latino and poor families from the city’s north side, as well as the increasing police abuses in their community. Shortly after the two met, they were arrested together while peacefully protesting at the Wicker Park Welfare Office.

“Fred took the Young Lords under his wing. He gave us the skills that we needed to come right out of the gang and start organizing the community,” Cha-Cha said in a 2019 interview with South Side Weekly. “We were already fighting for our rights in our neighborhoods, and we needed to form a united front. Our mission was self-determination for our barrios and all oppressed nations.”

It was a chance encounter that led the Young Patriots Organization, a leftist organization of Chicago’s mostly white migrants from Appalachia, into an alliance with the BPP and Young Lords. The YPO and a BPP leader were reportedly accidentally double-booked to speak at the same Lincoln Park church on the same night. There, they began to discuss the similar experiences of poor white migrants on the city's north side and that of its Black residents. Many in the YPO said they believed they were considered dangerous by the city and were treated unjustly by police, an experience all too familiar to Black Chicago residents.

With this common ground found, the groups formed an alliance, and the Rainbow Coalition was launched.

In the politically turbulent late 1960s, this movement toward unity and solidarity quickly caught on. In a matter of months, the coalition was joined by the Students for a Democratic Society, the pro-Chicano Brown Berets, the American Indian Movement, and the Chinese-American Red Guard Party, among others. Through direct action including strikes, protests, and demonstrations, the coalition worked together to fight poverty, corruption, police brutality, and campaign for housing justice.

The coalition also worked to end the violence between Chicago’s street gangs by brokering non-aggression pacts. In May of 1969, Hampton and the coalition managed to negotiate a truce between his group and the Blackstone Rangers and Black Disciples gangs. This truce was engineered as the FBI sought to stoke tension between the Rangers and the BPP by forging a note that the Panthers had put a hit out on Blackstone leader Jeff Fort, as was revealed years later in a Senate report.

The Rainbow Coalition grew and thrived in its direct action campaigns until the morning of Dec. 4, 1969, when Hampton was shot dead as he slept in a pre-dawn raid at his apartment by law enforcement officers executing a search warrant. Amid the shock of his killing, the Rainbow Coalition unofficially disbanded and some members went underground, fearing for their safety. As South Side Weekly’s Jaqueline Sarrato put it, with the killing of Hampton, “the feds had effectively crushed the 1960s’ most promising push for united, cohesive social resistance in Chicago.”

But the legacy of Hampton and the Rainbow Coalition resonates. In 1984, in the aftermath of his presidential bid, the Rev. Jackson founded the National Rainbow Coalition to push back against “Reaganomics” and consolidate a voting bloc around awareness of social programs, voting rights, and affirmative action. In 2012, it was the Obama campaign’s steadfast focus on coalition politics that propelled him to win a second presidential term. And today, Hampton and the Rainbow Coalition’s form of intersectional solidarity remains a cornerstone of grassroots organizing.