Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, breaking news, sweepstakes, and more!

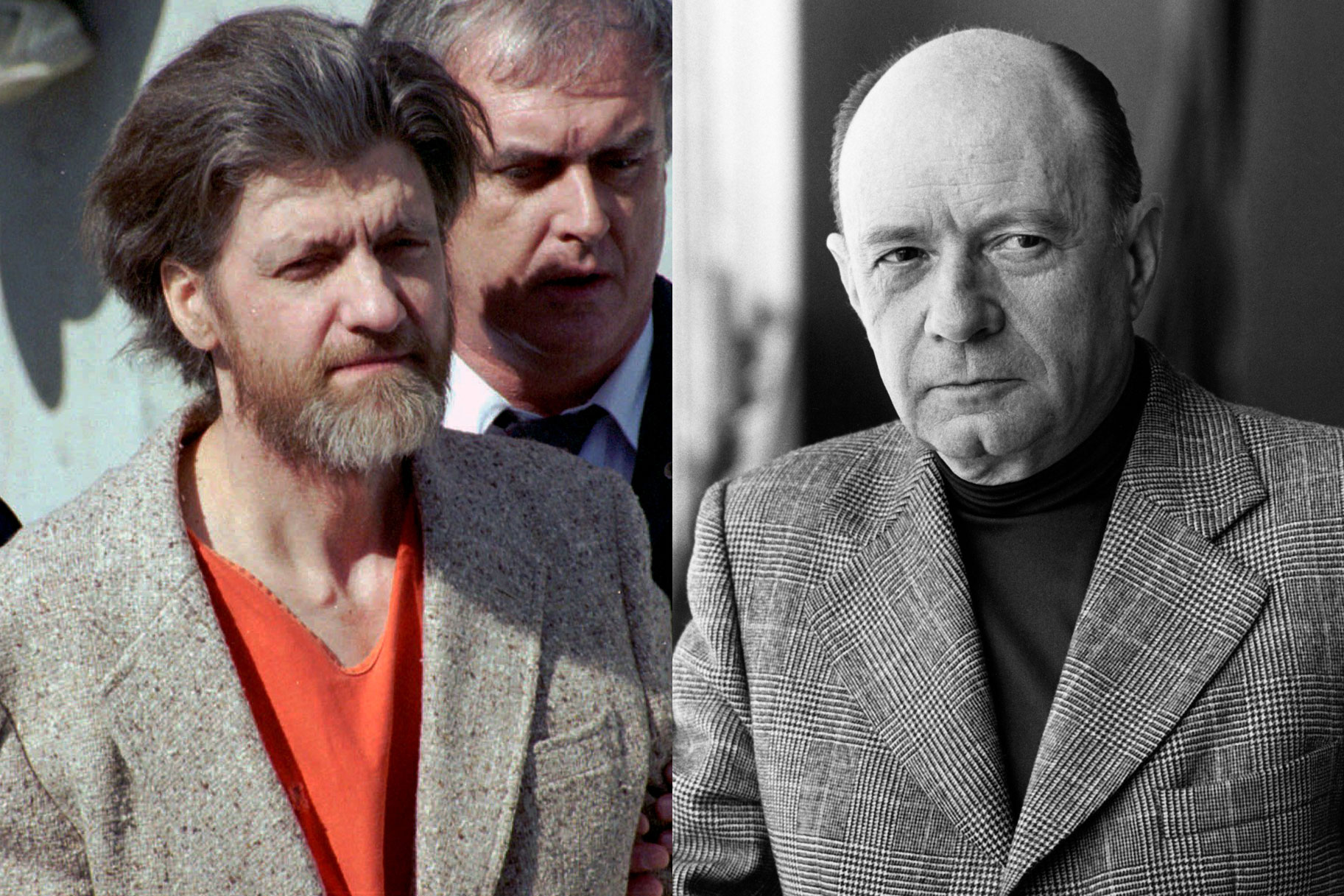

Who Was Philosopher Jacques Ellul And How Did His Writing Influence 'Unabomber' Ted Kaczynski?

Jacques Ellul was wary that technology was beginning to play an outsized role in people's daily lives, a belief that struck a chord with the man who would become the "Unabomber."

Unabomber Ted Kaczynski claimed that his series of mail bombings from 1978 to 1995 was a necessary evil to call attention to the negative effects technology has on humanity. So when he first encountered a written version of the ideas he had had for years, he quickly incorporated it into his deadly rationale and hate-filled manifesto, “Industrial Society and Its Future."

As outlined in the Netflix docu-series "Unabomber - In His Own Words," Kaczynski found his inspiration in French philosopher and Christian anarchist Jacques Ellul, who believed that technology should be used to serve humanity, not sustain it.

David Gill, president of the International Jacques Ellul Society, told Oxygen.com that Ellul preferred the word "technique" to explain his theories.

"What he was arguing is that technique is really a way of thinking about means rather than ends," Gill said. "[Ellul] thought ... we are dominated by more efficient means all the time, and losing sight of what the purpose is of this technology."

Ellul grew into these beliefs about humanity's relationship to technology -- in which humans increasingly use technology out of convenience, even as it negatively affects their innately human experiences -- later in his adult life. Born in Bordeaux, France on Jan. 6, 1912, he grew up in an impoverished but happy home. His mother worked as a private school teacher, while his father often found himself between jobs.

Ellul went on to graduate high school at the top of his class, and while he wanted to become a naval officer, his father pushed him study law instead. While attending the University of Bordeaux in 1930, he claimed that God appeared to him in a vision, though he never specified what he saw or was told, according to the International Jacques Ellul Society. By 1932, he announced he was Christian.

Ellul obtained his doctorate in 1936 and, after graduation, taught at a number of French higher education institutions. By 1940, he became an active participant in the anti-Nazi resistance movement during World War II. For his efforts to save Jewish men and women throughout the war, he was awarded the title "Righteous among the Nations" by Yad Vashem, The World Holocaust Remembrance Center in 2001.

Following in the footsteps of thinkers like Karl Marx and Søren Kierkegaard, Ellul became a prolific writer after the war.

Two of his most well-known pieces are "The Technological Society" and "Propaganda: The Formation of Men's Attitudes," published in 1954 and 1965, respectively.

John Sullins, secretary of the Society for Philosophy and Technology and professor of philosophy at Sonoma State University, explained in an email to Oxygen.com that Ellul's work, especially "The Technological Society," offered a "meditation" on technology's toll on humanity.

"What this means is that in return for the undeniable convenience and entertainment of technological life ... we are willing to trade in deeply meaningful aspects of our humanity," Sullins wrote. In other words, people become okay with potentially compromising privacy, family life and personal autonomy for the sake of making life easier.

Kaczynski, upon graduating from Harvard in 1962, picked up "The Technological Society."

"I had already developed at least 50% of the ideas of that book on my own, and ... when I read the book for the first time, I was delighted, because I thought, 'Here is someone who is saying what I have already been thinking," Kacynski recalled in 1998.

"[According to Kaczynski], the world is becoming just a giant machine destroying our humanity, and he found a solution in bombing," Gill said.

Sullins did emphasize that "while Ellul's writings may have played a role in the many different things that inspired Kaczynski, they are not the sole cause and what was done runs counter to my reading of what Ellul would have done himself."

Indeed, the key difference between Kaczynski and his philosophical inspiration is that whereas Kaczynski sought to overthrow technology by force (i.e., violent mail bombs directed at those he perceived as representative of the technological revolution), Ellul did not offer a solution. Instead, he only sought to diagnose what he saw as the problem.

Additionally, he never advocated for violence as a countermeasure, in the way that Kaczynski did.

"Ellul was a religious man and would never have condoned murder or violence under any circumstances," Sullins wrote.

Furthermore, Ellul did recognize that there was benefit to moderate use of technology.

"Ellul never opposed all participation in technology," Gill told The Boston Globe in 2012. "He didn't live in the woods, he lived in a nice house with electric lights. He didn't drive, but his wife did, and he rode in a car. But he knew how to create limits -- he was able to say 'no' to technology. So using the Internet isn't a contradiction. The point is that we have to say that there are limits."

"Technology is great in the toolbox of life, and bad on the throne of life," Gill further explained. "A tool is something we use for some purpose that we find life-giving and important; when it's on the throne, we use it just because we can or because technological leaders tell us to."

Ellul died on May 19, 1994, at the tail-end of Kaczynski's infamous bombing spree. But as indicated by the audio recordings of Kaczynski featured in the Netflix docu-series, he still adheres to Ellul's central belief that technology is a danger to human nature, but to a much more radical degree.