Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, breaking news, sweepstakes, and more!

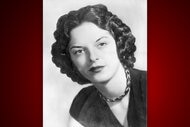

Looking Back At Trailblazing Federal Judge Constance Baker Motley, Who Played Huge Role In Dismantling Racial Segregation

Constance Baker Motley, the first Black woman appointed to the federal judiciary, put her safety on the line to dismantle racial segregation in Southern schools.

In honor of Black History Month, Oxygen.com is highlighting the stories of Black pioneers in justice.

Constance Baker Motley was no stranger to being first. She was the first African-American woman to serve in the New York State Senate, the first woman elected Manhattan borough president and the first African-American woman appointed to the federal judiciary. Above all, she was a fierce advocate for the civil rights movement, playing a key role in ending racial segregation.

Motley worked as a lawyer for the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund where she personally led the litigation that integrated of schools and parks in multiple Southern states, according to the United States Courts. In fact, Motley even wrote the original complaint in Brown v. Board of Education, the monumental 1954 case in which it was decided that "separate educational facilities are inherently unequal."

She became the first Black woman to ever argue a case before the Supreme Court and the cases she argued were pivotal for the civil rights movement. Through her litigation from the 1940s to the 1960s, she handled segregation issues at schools at all levels, from elementary to universities, in states like Mississippi, Alabama and Georgia. By the time she completed her work at the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund in 1965, Motley had personally argued 10 Supreme Court cases, winning nine. She also assisted in nearly 60 cases that reached the high court.

After her departure from the NAACP, she became the first African-American woman in the New York State Senate, and the first woman ever elected Manhattan Borough president.

She also became the first Black woman to serve as a federal judge. Then-President Lyndon Johnson first attempted to appoint her in 1966 and while she was eventually appointed, it did not come without an enormous pushback, according to the Columbia Law Review. Sen. James Eastland of Mississippi, the chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee and a man known for being a voice of the white South, held up Motley’s nomination for seven months. Eastland publicly opposed "Brown v. Board of Education" and was known for making racist comments about Black people, calling them an "inferior race."

While serving as a federal judge, she continued to pursue justice for both women and Black individuals. For example, she played an important role in a case brought in which female law school graduates claimed that prestigious law firms denied opportunities to women, CNN reports. The United States Courts notes that she overcame “Southern governors who literally barred the door to African-American students.”

“She opened up schools and parks to African-Americans, and successfully championed the rights of minorities to protest peacefully,” they stated in 2020. They also state that she consistently put her own safety at risk for the greater good.

Tomiko Brown-Nagin, the dean of the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University and author of "Civil Rights Queen: Constance Baker Motley and the Struggle for Equality," told CNN that Motley dealt with discrimination and disrespect from white lawyers and judges all along the way.

“When Motley was in Mississippi, a lawyer who defended the University of Mississippi refused to shake her hand,” Brown-Nagin recalled. “When she was working on one of the cases defending the Birmingham civil rights movement, she appeared in the courtroom, and the judge said, ‘Well, you're a woman. In other words, Why are you here?’”

Motley was raised in Connecticut by working-class immigrants from the West Indies and could not afford to go to college despite her aspirations to be a lawyer. Clarence Blakeslee, a New Haven philanthropist, paid for her education after being inspired by her.

“She [Motley] learned as a teenager the importance of compassion and developed then a belief that one committed person can make a difference in the world,” Judge Ann Claire Williams, wrote in a 2019 tribute to Motley.

Motley went on to excel in her educational endeavors, earning both a Bachelor of Arts degree in economics from New York University in 1943 and a Bachelor of Laws in 1946 from Columbia Law School.

While Motley's work may not be as well known as other civil rights leaders, she has become a pivotal source of change in America.

“I have to confess that I knew very little about her when I was in law school,” Laura Taylor Swain, who served as a law clerk for Motley, told the United States Courts. “I learned enough to know that she was someone very significant to our country’s history and to the history of my people.”

Motley died in 2005 at 87 of congestive heart failure. In 2011, she was posthumously awarded the 13th Ford Freedom Award.