Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, breaking news, sweepstakes, and more!

Where Are The MOVE 9, Who Spent Decades In Prison For Police Officer James Rump's Death, Now?

In the four decades since nine members of MOVE, a Black revolutionary group, were sent to prison for the shooting of Philadelphia police officer James Rump, some have died and the rest are adjusting to life outside of prison after being released on parole.

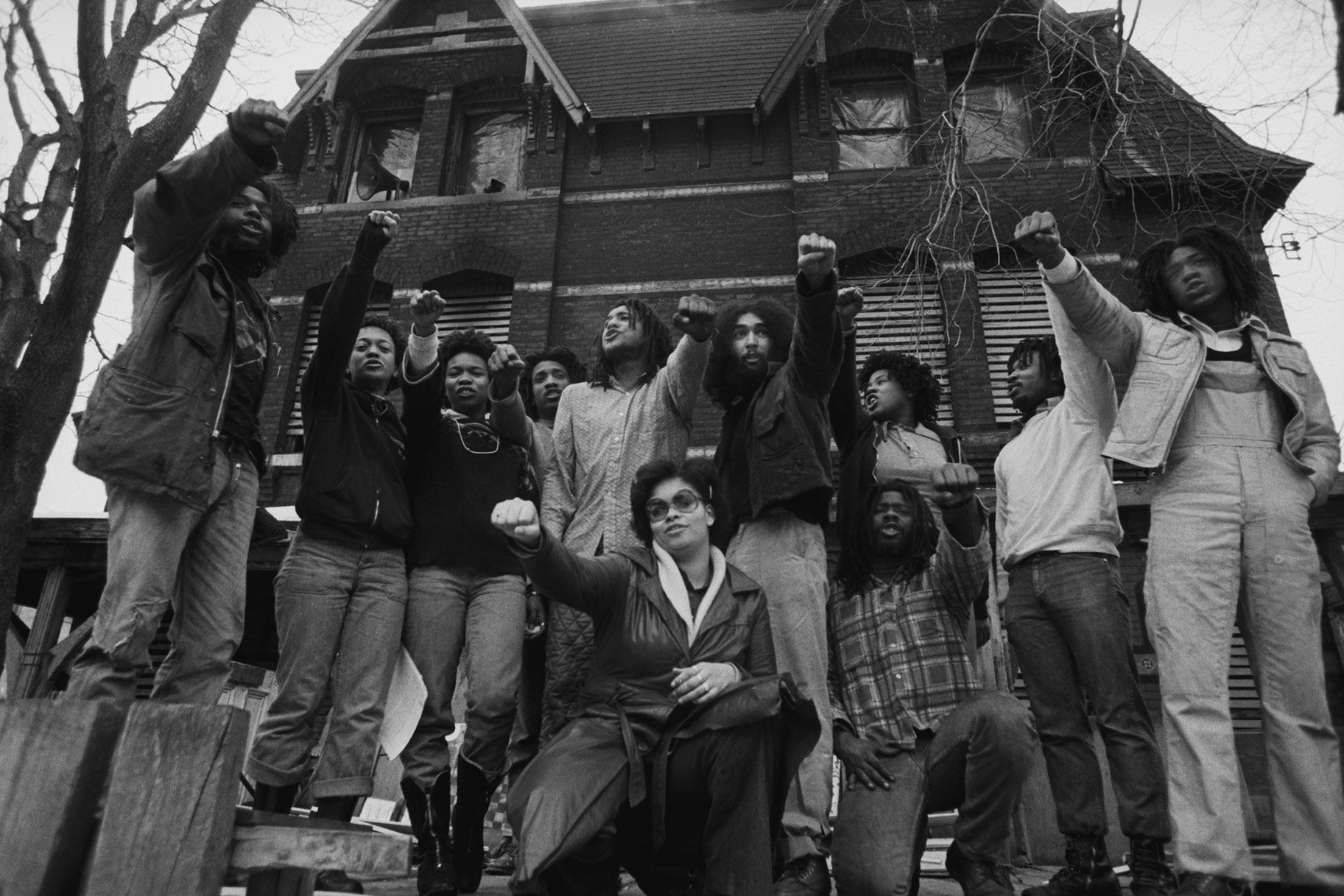

More than 40 years ago, the heated conflict between Black revolutionary back-to-nature group MOVE and Philadelphia police led to a deadly confrontation that would send nine MOVE members to prison for decades.

Tensions between the two long-standing adversaries reached a boiling point on the morning of Aug. 8, 1978 after the city's attempt to evict the group from their Powelton Village headquarters.

As 12 adult members of the anti-government, anti-corporation and anti-technology group huddled in the basement with their children, heavily armed police used a water cannon to flood the house with water, according to The Guardian.

“We were being battered with high-powered water and smoke was everywhere,” Debbie Sims Africa, later told the news outlet. “I couldn’t see my hands in front of my face and I was choking. I had to feel my way up the stairs to get out of the basement with my baby in my arms.”

Debbie had been pregnant and carrying her 2-year-old daughter Michelle.

For months before the standoff, MOVE members had been threatening to retaliate against police, while professing their views from a bullhorn outside of their home, dressed in fatigues and armed with rifles.

Just hours into the stand-off, the confrontation turned violent.

Around 8:15 a.m., a shot rang out, setting off a hail of gunfire that killed officer James Rump and injured another 18 police officers and firefighters, The Philadelphia Inquirer reported.

MOVE maintained that Rump had been killed by “friendly fire,” but authorities believed the fatal shot had been fired by members of the group, who embraced communal living and a back-to-nature philosophy.

All of the group members took the last name “Africa” to signify their decision to be a family and pay homage to their founder John Africa.

Nine members of the group—including Debbie and her partner Mike Africa—were ultimately convicted of third-degree murder and sentenced to 30 to 100 years in prison for the killing. Although Rump had only been killed by one bullet, the nine members, known as the “MOVE 9,” were ruled collectively responsible for the death.

The siege—and tensions leading up to the fatal altercation—are the subject of HBO’s new documentary “40 Years A Prisoner.” The film follows Mike Africa Jr., the son of Debbie and Mike Sr., as he tries to free his parents.

Both were granted parole in 2018, reuniting the family after four decades apart.

“I was so glad for Mike (Jr.) yesterday,” Mike Sr. said of his release and his son’s tireless efforts in the documentary. “Of course I wanted to be free, but I was so glad that he didn’t have that burden on him anymore.”

But just what happened to the surviving members of MOVE 9 in the years that followed?

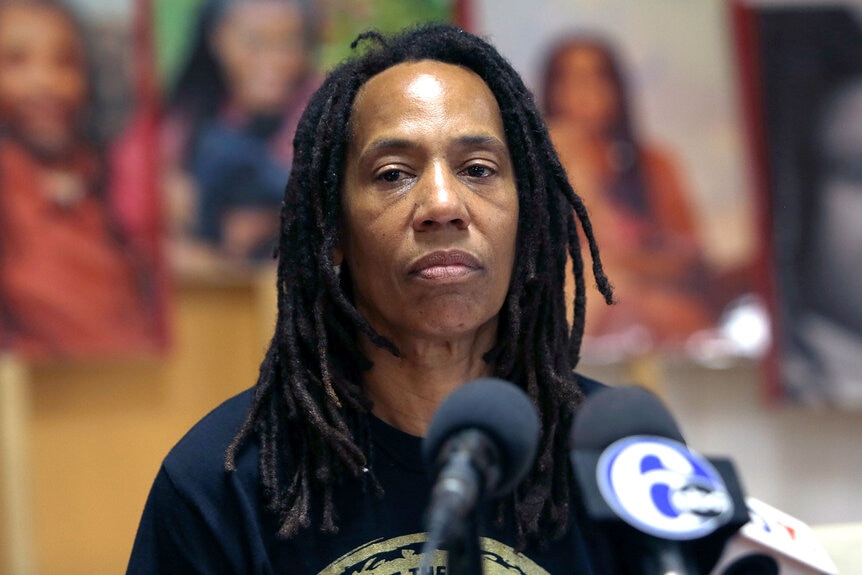

Debbie Sims Africa and Mike Davis Africa Sr.

Debbie was the first of the MOVE 9 to be released from prison on parole in June 2018 at the age of 62.

She had been just 22 years old when she was arrested and sentenced to prison for Rump’s death. Debbie gave birth to her son Mike Jr. while in prison about a month after the deadly siege and said after her release that having him taken away was the most difficult part of her prison sentence.

“The hardest thing was when the prison was directed to take me to a hospital so they could take him away after three days,” an emotional Debbie said, according to WHYY. “There are no words to describe it. Feeling that emptiness.”

While Debbie was elated to be released, she said it was difficult to leave MOVE members Janine Africa and Janet Africa behind. Although all three women faced the parole board at the same time, Debbie was initially the only one to be granted parole.

“The fact that I left prison and my sisters Janine and Janet didn’t—we came in on the same charges, we were arraigned the same, but when it came time to get out of prison, they didn’t do that the same. It’s a bittersweet victory for me,” she said.

After her release, Debbie went to live with the son she had once been forced to give up, and for the first time they were able to share a home together.

“This is huge for us personally,” she told The Guardian not long after her release.

The family would celebrate another reunion several months later, on Oct. 22, 2018, when Mike Sr. was also released from prison.

“I’m ecstatic coming from where I was just a couple of hours ago,” Mike Sr. told The Guardian after his release. “I wasn’t convinced in my mind that this would happen until I walked out the prison gates.”

Mike Sr. told WHYY that he believed he was finally granted parole—after unsuccessfully appearing before the parole board nine other times since 2008—because of his good behavior in prison.

“The main thing is staying out of trouble, right? That’s the main thing,” he said. “But I think my accomplishments came in the way of mentoring young guys coming through, and telling them to take a different look, go a different route.”

Although he and Debbie had not seen each other in 40 years—the couple remained committed to a life together.

“I missed her and I loved her,” he told The Guardian. “She’s been my girl since we were kids. That’s never wavered at all.”

Mike Sr. said the couple met in the summer of 1969 at a block party festival, according to The Philadelphia Tribune. Although Debbie was initially not interested, Mike Sr. was determined to win her affection.

The couple formally got married at The Sword of the Spirit Church in Lansdowne, Pennsylvania on April 6, 2019.

“Upon release from prison, one of the things that was on my list long since before prison was to marry Debbie,” he told The Tribune. “Prison forced me to wait 40 years longer than I wanted to. So, as soon as I got home, I began to talk to my son about it. He immediately started making phone calls and planning for the wedding.”

At the time of the nuptials, the couple was operating a nonprofit called The Seed of Wisdom Foundation.

“It’s a family-based organization that encourages young people to be healthy and fit,” Mike Sr. said.

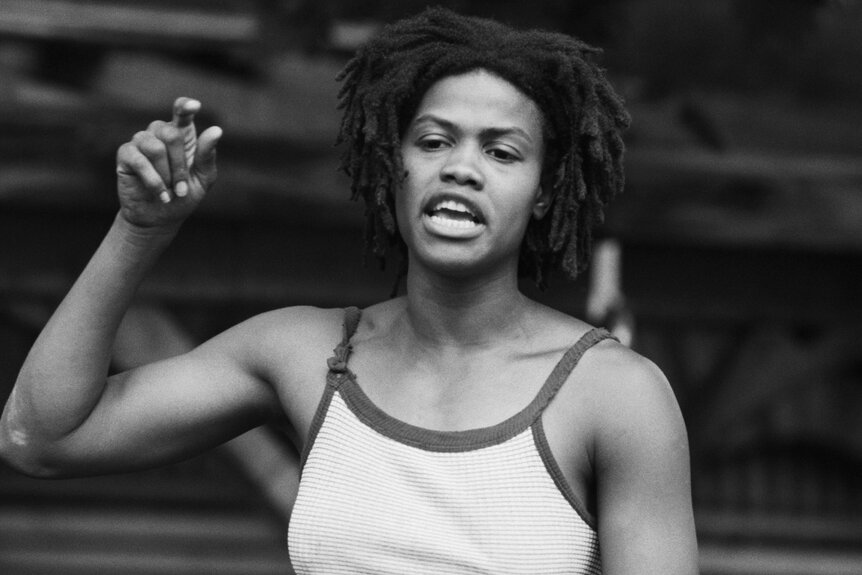

Janine Phillips Africa

Two years before the fatal siege that sent Janine Phillips Africa to prison, her newborn son was killed during an altercation with police at the MOVE headquarters in Philadelphia. According to MOVE members in the HBO documentary, police descended on the home on March 28, 1978 during a “big celebration” the group was having to celebrate the release of several of its members from jail.

Louise Africa said during the altercation police officers knocked Janine to the ground “crushing” the skull of her three-week old baby, a boy she had named Life. Then in 1985—seven years after she had been imprisoned—Janine lost a second son, 12-year-old Little Phil, in the 1985 city-led bombing of the MOVE compound, The Guardian reports. Little Phil was one of five children and six adults, including MOVE founder John Africa, who were killed in the bombing.

“I don’t like talking about the night Life was killed,” Janine wrote the news outlet from behind bars in 2018. “There are times when I think about Life and my son, Phil, but I don’t keep those thoughts in my mind long because they hurt.”

Janine wrote that the loss of her children only made her more committed to the group’s fight against police brutality.

“When I think about what this system has done to me and my family, it makes me even more committed to my belief,” she said.

Janine —who has long maintained her innocence—spent more than 40 years behind bars for Rump’s death. She said she survived the lengthy sentence by avoiding thinking about time.

“The years are not my focus,” she wrote The Guardian. “I keep my mind on my health and the things I need to do day by day.”

She also passed the time with her cellmates and fellow MOVE members Debbie Africa and Janet Holloway Africa.

“We read, we play cards, we watch TV,” she said. “We laugh a lot together, we’re sisters through and through.”

The women even trained a dog in their cell as part of a prison program training service dogs for disabled people.

The trio was separated in 2018 when Debbie was released on parole, but Janine and Janet later joined her on parole in May 2019, according to WHYY.

Janine told reporters shortly after her release that she believes police brutality is just as prevalent in today’s world as it was more than four decades ago.

“I’ve never seen people being shot down in the street in the back right in plain view on camera and nothing is done about it,” she said. “John Africa told us 40 years ago, it’s not going to get better, it’s going to get worse.”

Earlier this year, former Philadelphia Mayor W. Wilson Goode Sr. apologized for the 1985 bombing that killed Janine’s son in a British newspaper, according to ABC News. Although he said he was not directly involved in the decision to bomb the building, he accepted responsibility as the chief executive of the city at the time.

“There can never be an excuse for dropping an explosive from a helicopter on to a house with men, women and children inside and then letting the fire burn,” he wrote.

The apology, however, did little to satisfy Janine who called the apology “a lie.”

“I did 41 years for one day, and they never proved I killed anyone,” she said.

Janine currently serves as minister of education for MOVE, according to the group’s website.

Janet Holloway Africa

After more than 40 years behind bars, Janet Holloway Africa was released from prison in May 2019 alongside Janine Africa, her Black revolutionary “sister.”

Like Janine, Janet continues to be committed to MOVE and John Africa’s teachings and believes the government corruption the group opposed in the 1970s is still continuing today.

“People were looking at us like we were crazy,” she said, according to WHYY. “You just couldn’t see it because they were covering it up, they were not exposing it.”

According to a biography on MOVE’s website, Janet found solace in the group as a young mother in the 1970s.

“I remember sitting in my rocking chair with my newborn baby in my arms feeling the same way my mother felt, wanting something better for my daughter, wanting her to be safe, happy, free of the hurt, pain, disappointment and disillusion of this cold, cruel, prejudiced system,” she said of her struggle to find contentment before joining the group.

After hearing about the group through word of mouth, she said she was drawn to the “clean righteousness” of the fight for reform.

MOVE “changed my life forever,” she said.

Merle Africa

Merle Africa died in prison in March 1998, according to The Philadelphia Inquirer. Few details were available about how she died. MOVE said on its website the organization believed the death was “highly suspicious.” Prison officials reportedly told members Merle had died from natural causes, MOVE said.

Phil Africa

Phil Africa, a once high-ranking member of MOVE, died at a Pennsylvania state prison in 2015, according to The New York Times. Phil, who had been born with the name William Phillips, was 59 years old.

Prison spokesperson Robin Lucas attributed the death to unspecified natural causes.

Ramona Africa—the lone adult survivor of the 1985 bombing—called the death “suspicious” on MOVE’s website.

She said Phil hadn’t been feeling well but was also spotted by other inmates stretching and doing jumping jacks. MOVE members tried to visit him, but were not allowed. Ramona said Phil was transported to the hospital where they kept him “incommunicado” for five days. When members were allowed to see him, days later, she said he was “incoherent” and couldn’t talk. He died later that day.

Ramona remembered Phil, who she said had been married to Janine for 44 years, as a talented painter who “created countless paintings which he sent to supporters” and was often laughing and smiling.

“He was a warm father figure to many in prison where he taught inmates how to box, to think, and how to get stronger,” she wrote.

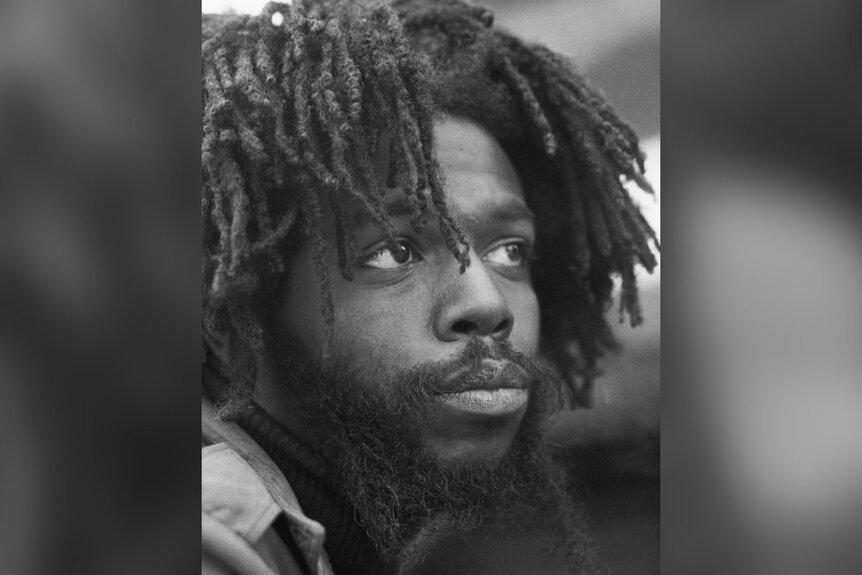

Delbert Orr Africa

Delbert Orr Africa was released from prison in January 2020—but his life of freedom would be short-lived. Delbert died months later in June 2020 from what his daughter Yvonne Orr-El told The Philadelphia Inquirer was prostate and bone cancer. She alleged that while behind bars, Delbert had started to exhibit symptoms of the disease but was not treated for another 18 months.

“Had my father received the treatment he needed, the healthy, strong, smiling, humorous, sarcastic man that I called my father would still be here today,” she said.

A spokesperson from the Department of Corrections declined to discuss specifics of Delbert’s case but told the paper that the department “provides medical care that is in line with community standards.”

Delbert was captured in iconic images depicting the black liberation movement. After the gunfire in 1978, Delbert emerged from the MOVE headquarters shirtless and unarmed with his hands out-stretched, but he was viciously beaten by three police officers.

“A cop hit me with his helmet. Smashed my eye. Another cop swung his shotgun and broke my jaw. I went down, and after that I don’t remember anything till I came to and a dude was dragging me by my hair and cops started kicking me in the head,” he would later tell The Guardian in a series of letters from prison.

Delbert suffered a broken jaw and broken ribs, among other injuries, according to WHYY. Three officers were arrested and charged with beating Delbert, but a judge would later throw the case out.

Years later, while behind bars, Delbert’s 13-year-old daughter Delisha was killed in the 1985 bombing on MOVE headquarters.

“I just cried,” Delbert told The Guardian of hearing the news. “I just wanted to strike out. I wanted to wreck as much havoc as I could until they put me down. That anger, it brought such a feeling of helplessness. Like, dang! What to do now? Dark times.”

Despite the tragedies, Delbert remained committed to MOVE after his release and even referenced his efforts in his last words, according to Mike Jr.

“He said, ‘I tried my best to be a good soldier,” Mike Jr. told WHYY. “Even though he felt pain, even though he was hurt, he didn’t give up and he wanted to inspire other people with his example.”

Eddie Goodman Africa

In June 2019, Eddie Goodman Africa was released from Phoenix prison in Pennsylvania after more than four decades in prison, according to The Guardian.

“This is a significant victory and day of celebration for us as a legal team, but more importantly for Eddie, his loved ones, and the movement supporting the MOVE 9,” attorney Brad Thomson told the outlet following the release.

Eddie’s legal team had argued to the parole board that he should be released, in part, because of the work he had done behind bars to mentor younger prisoners. He also coached sports teams and led exercise programs in prison.

His last infraction for “refusing to obey an order” came in March 2004 after he resisted prison officials who were trying to cut his dreadlocks, the outlet reports. Eddie was later allowed to keep the hairstyle after arguing that it was part of his spiritual and cultural beliefs.

Chuck Sims Africa

Chuck Sims Africa was the final member of the MOVE 9 to be released from prison after he was granted parole in February of 2020, The Guardian reports.

Chuck, who is Debbie’s younger brother, had also been the youngest member of the group imprisoned for Rump’s death. He was just 18 years old when he was taken to jail.

Shortly after his release, attorney Brad Thomson told The Associated Press that Chuck was spending time with his family.

Mike Jr. said his uncle’s release finally put an end to the decades long fight to free the incarcerated MOVE members.

“We will never have to shout ‘Free the MOVE 9!’ ever again,” Mike Jr. said. “It’s been 41 years, and now we’ll never have to say it.”