Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, breaking news, sweepstakes, and more!

3 Brothers Armed With Shotguns Killed 4 South Dakota Teens In A ‘Mind-Blowing’ Mass Murder

Campfire revelry for five innocent South Dakota teenagers turned deadly when three cold-hearted brothers shot to kill. The lone survivor lived to see justice done.

They were young and out for a good time.

The evening of November 17, 1973 started out as just another carefree chance for five Sioux Falls, South Dakota teenagers to hang out under a night sky at Gitchie Manitou State Park. It was a quick drive, just over the border in nearby Iowa.

By the following morning, four boys were dead, a girl had been raped, and one of the worst crimes in Great Plains’ history would leave a bloody, painful, and ugly stain that’s never gone away.

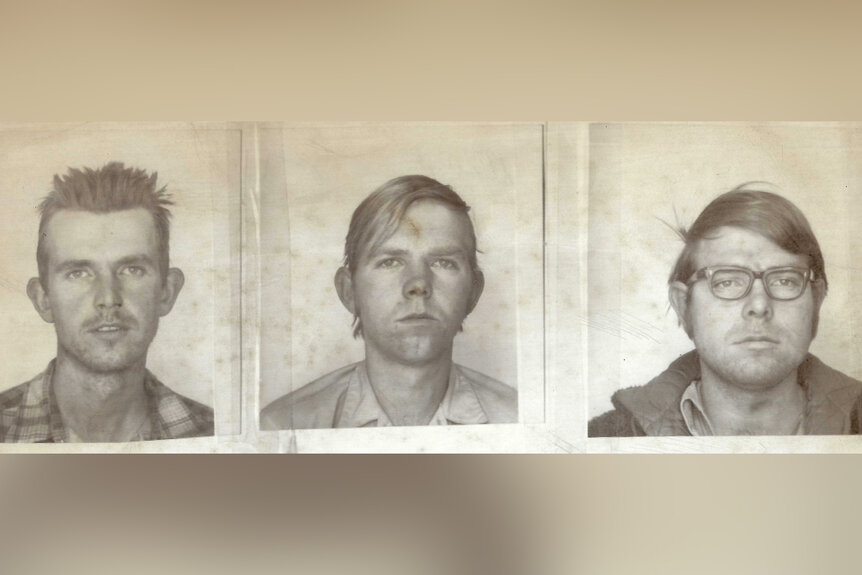

The mass murders were triply heinous because the perpetrators of the brutal acts were three cold-hearted brothers: Allen Fryer, 29, David Fryer, 24, and James Fryer, 21.

The siblings came to the park armed with shotguns and “played off each other” to escalate the violence, authorities told Oxygen’s “Killer Siblings,” airing Saturdays at 6/5c on Oxygen.

Stewart Baade, 18, his brother, Dana, 14, Mike Hadrath, 15, Roger Essem, 17, and Sandra Cheskey, 13, who was dating Essem, had headed to the wooded park preserve on the South Dakota-Iowa border to chill out around a crackling campfire. They brought guitars to strum and a joint to smoke, and were minding their own business, the Argus Leader reported in 2013.

The next day a couple taking a car out for a test drive in the park preserve was horrified when they came upon the bodies of the dead adolescents, according to a 2014 Estherville News article.

The mass murder — exceptionally unusual this area — became a unified team effort by law enforcement and an “army of investigators.” Members of the South Dakota Police Department worked alongside special agents from the Iowa Division of Criminal Investigation, also known as the state’s “Detective Bureau.”

Investigators combed through the leafy crime scene. Gaping bullet wounds in the teens’ bodies signaled to investigators that the victims had been blasted by shotguns at “close range,” they told “Killer Siblings.”

Spent shell casings were recovered and determined to be from 12-, 16-, and 20-gauge shotguns. Investigators reasoned that there could have been not just one, but three killers.

Authorities also recognized that Stewart Baade’s 1967 blue van that the five friends came to the preserve in was nowhere to be found. An urgent search went out to find the vehicle, which ultimately ended up being a dead end for leads.

In the meantime, Cheskey, the lone survivor in the group, detailed the events of the night of the deadly shooting to authorities. She said as they were partying, they heard twigs snapping in the distance.

Essem went to investigate the noise and the whole night tragically changed. He was shot and fell to the ground. More gunshots followed.

Stewart and Hadrath were wounded. The Fryers then emerged from the darkness, falsely identifying themselves as narcotics agents who were there to bust them for the marijuana.

In fact, the investigation revealed that the armed brothers had come to the wooded preserve to poach deer. When they spied the teenagers partying they turned their sights on them — and their marijuana.

One of the three men, who called himself “the boss” — later identified as Allen — ordered Cheskey to get into his truck. That was the last time she saw her friends alive. Investigators theorized that after she left, the Fryers left on the scene lined the teens up and killed them.

After driving around with Cheskey, Allen met up with his brothers at a farmhouse, where James sexually assaulted Cheskey.

After the rape, Allen took Cheskey home. He told her that he would kill her if she told anyone about what had happened. The next morning, she discovered her four friends were dead, and she overcame her fear to go to the authorities.

Cheskey worked with investigators, sharing descriptions of the men and their truck. She rode along all over the area with officials in search of the farmhouse where she’d been assaulted.

Cheskey’s descriptions enabled investigators to create sketches of the suspects. They were distributed, but failed to turn up any productive leads. As time went by investigators were concerned. “It did seem helpless,” they told producers.

On Nov. 29, officials got the break they desperately needed. During a ride-along Cheskey spotted the farmhouse where she was raped. As authorities investigated, Allen drove by. “That’s him, that’s the boss,” Cheskey screamed at the time, she told producers.

Cheskey would go on to identify the killers in a lineup, where she learned that the three men were brothers. “It was just mind-blowing,” she told producers.

As one investigator put it: The game was up for them.

“Three brothers were captured without resistance and charged with murder in the shotgun slayings of four Sioux Falls teen-agers Nov. 17,” The New York Times reported on Nov. 30.

Profiles of the homicidal suspects emerged. Family dysfunction ran deep, as did violent personalities. Their father referred to the three brothers as his “chore boys.” They shared a pack mentality.

“They were criminals when they were in each other’s presence,” Phil Hamman, co-author of two books about the crimes, told producers. “For the Fryer brothers life was all about what was going to be the next crime, what could they steal next and what could they go out and shoot next.”

After their arrests, the Fryer brothers turned on each other to shake the blame off themselves. “Each was accusing the other of pulling the trigger,” investigators told producers.

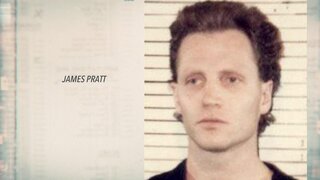

James had been in a scrape with the law and serving time in jail when the murders were committed. He tried to claim that as an excuse but was unsuccessful because on Nov. 17, he was able to get out of lockup thanks to a work release program. He could have been at Gitchie Manitou State Park with his brothers.

In Feb. 1974, three months after the murders, David was the first sibling to be tried. He was found guilty and sentenced to life without the possibility of parole.

Three months, later Allen was found guilty of four counts of murder and received four life sentences. In a bizarre twist, after this Allen and James escaped from jail and were on the lam for nearly a week before being captured.

But in Dec. 1974, James Fryer was found guilty of first-degree murder and manslaughter and sentenced to life in prison. The case was over.

The Fryer brothers who killed together are still together. They are serving life sentences at the Iowa State Penitentiary in Fort Madison.

To learn more about the case, watch Oxygen's “Killer Siblings” on Saturdays at 6/5c on Oxygen or stream the series on Oxygen.com.